2 December 2023. Here is the second part of my Substack serialisation of Chapter Six of Psychedelic Tricksters: A True Secret History of LSD (Amazon. Also on Kindle: HERE) The first part of the serialisation is available HERE. – D.B.

Owsley Fights Prohibition

On January 22 1966 Ken Kesey fled to Mexico to avoid a six-month prison sentence for possession of marijuana. In his absence, the Merry Pranksters were led by Ken Babbs. The California Acid Tests ended in October 1966, when new legislation was enacted. The Drug Abuse Control Act of 1965 passed by the United States Congress empowered the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare to designate LSD as a controlled substance, requiring licensing for sales and distribution.

Although this new federal law allowed possession for personal consumption, the California State Senate clamped down further and made possession of LSD a misdemeanor punishable by a maximum fine of $1,000 or a year in jail, and made manufacture and possession for sale a felony punishable by one to five years in prison. Other states followed with similar legislation. In 1968 the United States Congress made possession a misdemeanour and sale and manufacture a felony throughout the USA.

The Bureau of Drug Abuse Control (BDAC) was formed in February 1966 as a part of the United States Food and Drug Administration. In 1968, the BDAC was merged with the Federal Bureau of Narcotics to form the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD), forerunner of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), which was established in July 1973.

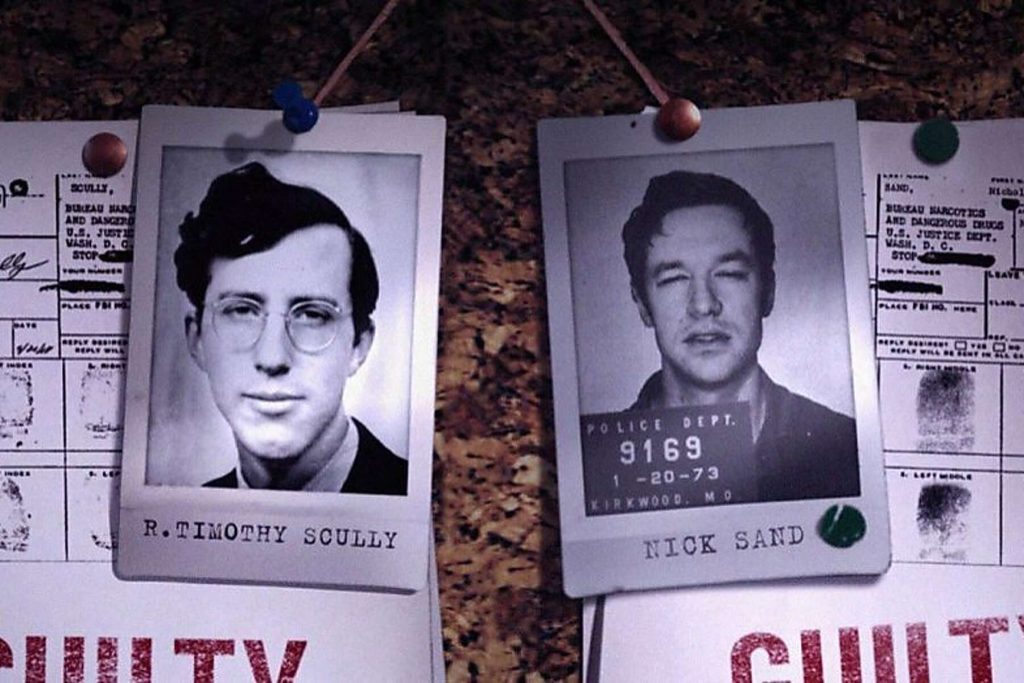

Owsley/Bear Stanley was undeterred by the New Prohibition, as was his assistant, Time Scully, who wanted more than anything to work with him in making LSD. Scully’s wish was soon granted. In July 1966, Bear and Melissa Cargill set up a laboratory in Point Richmond, California with Scully and Don Douglas. Owsley had got as far as making a very pure crystal LSD, and obtained new equipment for tableting it. This became known as ‘White Lightning’. With Scully he succeeded in creating about 100 grams of LSD which made about 300,000 white lightning 300 μg tablets in addition to some handmade tablet triturates.The laboratory was also used to make DMT (N,N-Dimethyltryptamine), a synthetic version of a resinous South American tree bark with hallucinogenic properties.

Bear, having produced such a large run of LSD, was ready for a break, but Scully was keen to continue the work. Scully collected the material and equipment for a prospective new lab from various companies in the San Francisco area which Bear had recommended. Unknown to Scully however, the Bay Area BDAC had been asking local chemical suppliers to alert them to anyone ordering materials that might be used for LSD production.

On December 8, 1966 Scully called at a Bay Area chemical firm to collect some chemicals he had ordered. The man at the sales-desk helped load the purchases into his truck. Scully then walked home, leaving his colleague, Don Douglas, to drive away the truck. Douglas, as he drove off, noticed that the ‘sales-desk man’ jumped into a car and began following him. Knowing they had a surveillance tail caused some soul-searching, but Scully and Douglas decided that the BDAC agents were unlikely to act unless they were led to a laboratory; and as yet, there wasn’t one. But, shortly before Christmas 1966, Scully rented a house at 4210 East 26th Ave, near Denver City Park, to accommodate his first laboratory. As a cover story, he told the owner of the property that he was doing work in the basement with radio isotopes on a government licence which required special security.

In preparation for getting the Denver lab operational, the two chemists continued to gather equipment and chemicals in California, and did so under the eyes of the BDAC agents, to whom they would cheekily wave at in the street. Finally, on January 19, 1967 the truck was loaded up for the thousand-mile journey to Denver, Colorado. Scully and Douglas, having observed the tailing-techniques of the BDAC for some weeks, implemented a plan to shake off the surveillance. In the side streets of San Jose they succeeded in losing their BDAC tail and drove the truck to Denver.

Once the Denver facilities were in place Scully returned to San Francisco to collect a consignment of Bear Stanley’s lysergic acid. Bear however, had forgotten the false name he used for the Arizona safety deposit box in which he had stashed it. He did not admit his memory lapse; instead he told Scully that, given the heat he and Don Douglas had encountered when gathering chemicals and equipment, his ‘intuition’ told him to leave LSD production aside for the moment. In early 1967, chemist Sasha Shulgin had given Bear Stanley a small sample of STP (STP-2,5-Dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine) and a sketchy outline of the synthesis for making it. Bear insisted that Scully try to work out the process for making STP – which was still legal – from Shulgin’s sketchy notes and paid for the chemicals and equipment.

Nick Sand

Bear, while visiting New York in the fall of 1966, had met Nick Sand, who was cooking DMT there in a lab. Sand was born in 1941, the son of New York communists Clarence Hiskey and Marcia Sand. During World War II, Clarence worked as a chemist on the Manhattan project, but was dismissed in 1944 after army counter-intelligence observed him meeting a known Soviet spy named Arthur Adams. In 1948 Clarence and Marcia were called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, but refused to testify about their friends. They were both cited for contempt, which cost Clarence his job at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. In 1953, Clarence was subpoenaed to testify before a closed session of the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations, in which he was interrogated by Senator Joseph McCarthy and Donald Trump’s future lawyer, Roy Cohn. Due to lack of evidence, neither Clarence nor Marcia were prosecuted. Nick didn’t inherit his parents’ politics but he did inherit their rebellious, anti-establishment spirit and his father’s interest in chemistry. Nick enrolled at Brooklyn College night school to study sociology and anthropology in 1962 and graduated in 1966. During this period he taught himself chemistry and founded Bell Perfume Labs as a front for manufacturing DMT.

In 1964, Nick Sand met Richard Alpert at a lecture at Brooklyn College and turned him on to DMT. Alpert in return invited Sand to visit Millbrook and experience his first LSD trip. Alpert also introduced Sand to the writings of the Armenian mystical philosopher, George Gurdjieff, which profoundly influenced his thinking. Sand recruited former UC Berkeley organic chemistry student David Mantell to work at Bell Perfume Lab on purifying DMT and DET (diethyltryptamine). In September of 1966, Timothy Leary ceremoniously ‘appointed’ Sand as alchemist for the League for Spiritual Discovery and signed a document instructing law enforcement officials not to impede his work.

Sand, unlike Scully, treated the venture as a profit-making business. Sand, nonetheless, was an idealist, if also a fanatic. He recalled that during a pioneering trip, ‘… suddenly a voice came through my body that said your job on this planet is to make psychedelics and turn on the world. It was very interesting’. Sand, Scully, Bear Stanley and their psychedelic co-thinkers were deeply concerned with the immediate threat of global thermo-nuclear confrontation war and with the Vietnam War. Scully recalls:

‘When I was working with Bear, he and I took an acid trip with Richard Alpert one day in 1967 where we were planning the strategy of turning on the world, modest as we were, and one of the things we agreed on was that if we just turned on the United States it would be like unilateral disarmament. We really had to make sure that every country in the world got turned on, particularly those behind the Iron Curtain, or else it would be a very bad thing geopolitically. And so we talked to the Brotherhood [his later colleagues, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love – see below] and they made an effort to spread it around the world. And they did get our LSD into Vietnam and behind the Iron Curtain and all over’.

Nick Sand recalled of himself:

‘I was considered as some sort of mad man psychedelic commando because I’d go anywhere, do anything… If we could turn on everyone in the world then maybe we’d have a new world of peace and love. We had the insane desire to risk our freedom and be what we thought were American patriots’.

Tim Scully, for his part, favoured system-change. He was concerned about racial, economic and sexual inequality; laissez-faire capitalism; runaway environmental disasters; overpopulation; and more. He believed that if enough people took LSD they would be gentler with each other and with the environment, and less trusting of large organizations, including governments and large corporations.

Owsley suggested to Nick Sand that he move to California. In February 1967, Sand and David Mantell dismantled Bell Perfume Labs, packed the equipment into a used meat truck, and lit out for California with a plan to install it at a ranch in Cloverdale that Mantell rented. On April 3 their truck was pulled up by the police when Sand failed to stop at a weighing station in Dinosaur, Colorado. As Sand refused to pay a fine to the arresting officer, he and Mantell were jailed. A search of the truck yielded chemicals and laboratory equipment. The local sheriff’s office and BDAC proudly announced they had discovered a ‘mobile laboratory’ with 20 lb. of ‘LSD’, valued initially at $336 million. But as the drug had only been partially processed, the estimate rapidly dropped to $1.5 million. Also, as the search had been carried out without a warrant it was later ruled to have been unlawful; charges were dropped and the truck’s contents were returned to Sand two years later.

In a tragic accident which seems to have occurred just after Sand and Mantell left New York, Alan Bell of the Bell Perfume Lab died sleeping in an attic in New York when a candle fell over and ignited some decorative fabric hangings. Finally Sand and Mantell arrived in San Francisco. Bear introduced Sand to Scully and asked Scully to tell Sand everything he had learned about making STP. Sand had lost his chemicals and lab equipment in the bust in Colorado, but he still had a good supply of Bear’s White Lightning LSD stashed in New York, which he would sell during the 1967 Summer of Love.

According to Tendler and May’s book, The Brotherhood, at least some of this was distributed by the Hell’s Angels in batches worth sales of $50,000 in exchange for $40,000. Sand used the money he made from selling White Lightning to establish his D&H Custom Research lab in San Francisco, where he and Mantell made STP. To make STP he initially used small-scale table top glassware but soon scaled up his production so by early 1968 he was cooking larger batches of STP in a surplus 200-gallon stainless steel soup kettle. Scully’s Denver laboratory produced at least 2 lbs of STP before Bear finally remembered the name he had used for the safe deposit box containing his stash of lysergic acid. In the early autumn of 1967, production of LSD resumed. As distributors, Bear used the Oakland Hell’s Angels motorcycle gang, who he had met through Ken Kesey.

Profits from Bear’s productions accumulated rapidly. On a trip to Millbrook, Bear was stopped near the estate by police who found a safe-deposit key for his money-stash in New York which was regularly topped by Melissa Cargill. Timothy Leary suggested to Bear that he turn to banker Billy Hitchcock for help. Hitchcock called Bill Sayad, a banker at Fiduciary Trust at Nassau in the Bahamas. Sayad flew to Manhattan to pick up the money and open the account for Bear, under the name ‘Robin Goodfellow’. Tendler and May say that by winter of 1967 Bear had ‘$320,000 in safe deposit boxes around San Francisco’ as well as $225,000 ‘moved abroad, courtesy of Billy Hitchcock’.

In late September or early October 1967, Scully closed his first Denver lab. The BDAC never discovered it. Bear, having paid for all the raw material for the several hundred grams of acid produced there, stashed the whole product. He now wanted to get the LSD tableted and withdraw from LSD production. In October 1967, he told Scully, who was looking to establish another LSD lab, ‘You’re on your own’. Unfortunately for Bear, the BDAC tracked a dealer who did tableting for him back to his tableting facility in Orinda, California.

On December 21 1967, six BDAC agents broke down Bear’s door. Five people, including Bear and Melissa Cargill, were arrested. The agents seized 67.58 grams of LSD, and 161 grams of STP (which was still legal), plus laboratory equipment. The police were less than thorough in their search, and Bear got some of his Hell’s Angels contacts to go in and recover items the police had missed. He also sold the Hell’s Angels some of the LSD he had stashed well away from his Orinda facility. Bear resumed working for the Grateful Dead as their sound engineer until the case came to court in September 1969, and the Orinda defendants were convicted and given three consecutive one-year sentences. Bear Stanley would be confined to a federal prison from 1970 to 1972.

Scully needed investment money to obtain enough raw materials to set up another lab. Bear suggested he try Billy Hitchcock, newly ensconced at a retreat in Sausalito, California. The authors of both Acid Dreams and The Brotherhood claim that Hitchcock only agreed to loan Scully the money to restart LSD production on condition that he dropped a plan to give the product away free. It is true that in October 1967 Scully asked Hitchcock to finance the production and free distribution of enough LSD (about 200kg) for everyone in the world who wanted it to try it. Hitchcock did not feel able to finance the plan, because he didn’t have enough cash to do so (much of his money was tied up in a trust); and because he believed that people would not value something they didn’t have to pay for. Scully recalls ‘he did loan me a small amount of money ($11,000) at 300% interest to help finance the next lab. But he was in no way “Mr. Big” and he didn’t dictate any terms to me or anyone else for making LSD’.

The British Connection

Nick Sand and Tim Scully searched for European sources of lysergic acid and ergot alkaloids. During the years in which it was still legal to do so, Englishman Michael Druce had supplied the Millbrook fraternity with LSD by mail-order through Michael O’Dwyer Ltd, a small chemical company based in Hampshire, England, in which he held a majority share.

After the Swiss Sandoz company restricted sales to the U.S. in 1962, Druce imported LSD from the Czechoslovakian state-owned pharmaceutical firm, Chemapol, via its export wing, Exico. The Czechs, no longer bothered by the expired Sandoz patent, were producing LSD in 1 milligram vials for small orders or in 100-milligram ampoules of powder for bulk purchases. During this period, Druce’s future partner, Ronald Craze, was handling Exico’s business in London. After use of LSD was made illegal in Britain, Druce stopped exporting it. But, his prospective American customers wondered, would he be prepared to procure and export raw materials and specialist lab equipment for LSD production, if the end-users were beyond British jurisdiction? Hitchcock suggested to Tim Scully that Druce might be amenable to such an idea. As it turned out, he was. Druce and Craze were established commodity brokers and traders, storing merchandise against price rises until it could be sold on at a profit. Specialising in chemicals, they could – unlike Sand and Scully – approach producers direct. Scully, with Donald Munson, an expert organiser of smuggling operations, arranged to get the chemicals to the United States.

Scully, with the money supplied by Billy Hitchcock, was able to make his first purchases from Druce in late January 1968. Scully paid Druce $9,000 for 2.8 kilos of ergotamine tartrate, which was sent to the United States, mis-labelled as ‘CQ equipment for gas chromatography’ to fool the customs, and picked up at a chemical firm in South Carolina, by someone on behalf of ‘Tim Philips’, the name Scully used in London.* At same time Druce supplied Scully with 250 grams of lysergic acid. This was sent to the US via a courier, Ayman de Sales, who smuggled it to Montréal and then to New York. However, when Scully tried to use the lysergic acid to make LSD he found it was bogus – about as useful as talcum powder. Scully appealed to Druce for a replacement. A few weeks later Druce managed to locate a kilo of the real thing real and offered it to Scully for the cost of three quarters of a kilo. As Scully didn’t have the money to pay for it he shared the kilo with Nick Sand. Sand who bought 500 grams and Scully got a good deal in paying for 250 grams and getting 500. When Sand and Scully went to collect the kilo of lysergic acid from Druce in England, Scully brought along for good measure a melting point tester which could verify that the product was sound. Some of the consignment was stashed in a Zürich safe deposit box; and some was concealed in a teddy bear which Scully mailed to his mother’s address in the US.

Scully Feels the Heat

In February 1968 Tim Scully, with assistants Rory Condon and Ruth Pahkala, opened a second Denver lab at 1050 South Elmira Street. The house was rented by Condon under an alias. In the LSD purification process, Scully was able to demonstrate a phenomenon known as ‘piezoluminescence’, which had been worked out by Owsley on a small-scale. In piezoluminescence, LSD crystals are so pure that they give off flashes of light when shaken, stirred or crushed. In the spring of 1968, Scully, using the ergotamine tartrate he had bought from Druce, made about 20 grams of LSD in his second Denver lab and made an arrangement with Sand to have it tableted. Scully believes that Sand sold some of it to the Brotherhood of Eternal Love for distribution.

In June, Scully took a trip from Denver to San Francisco. Unfortunately, while he was gone the grass on his lawn began to turn dry yellow. The house, being in a suburb where city water was not yet available, had its own well and septic tank; but the well pump failed and the grass couldn’t be watered. The neighbours, who liked everyone in the street to keep up appearances with nice green lawns, were becoming restless and curious. Scully’s two assistants flew to San Francisco to report the problem. Scully told them to return and get the pump fixed. But before they got back their landlord, a Mr Chance, was out and about looking over the various properties he owned in the neighbourhood when he noticed that the lawn had turned brown. Mr Chance walked round the empty property and noticed a very bad smell, which he feared was emanating from a dead body. He called the police, who broke in and traced the smell to spilt chemicals in the basement.

The next day, police scientists identified small samples of very high-quality LSD left there. In San Francisco, Scully, after hearing nothing from his assistants about the problem with the lawn, telephoned his Denver lab. When a voice answered ‘Scully residence’, he knew immediately it had been raided, because he could only have been identified from documents lying around bearing his real name. As Scully didn’t know where his assistants were he couldn’t warn them to stay away, although he hoped reports of the raid in the local press might have alerted them. But four days after the laboratory had been discovered, Condon and Pakhula returned, blissfully unaware of what had happened, and were arrested. Scully, having escaped arrest, lost all his lab equipment. However, the raw materials he and Nick Sand had bought from Druce and Craze were not captured in the bust; and Scully still had some chemicals he had ordered through Nick’s company, D&H Custom Research. Nick Sand eventually agreed to finance setting up a new lab for making LSD in return for Tim Scully teaching him the process he had learned from Owsley Stanley.

Next up: (continuing this chapter) The LSD chemists team up with the Brotherhood of Eternal Love.