(January 2022)

(January 2022)

How Walt Whitman’s Poetry Came to England

By David Black

Suddenly, out of its stale and drowsy air, the air of slaves,

Like lightning Europe le’pt forth,

Sombre, superb and terrible,

As Ahimoth, brother of Death.

God, ‘twas delicious!

That brief, tight, glorious grip

Upon the throats of kings.

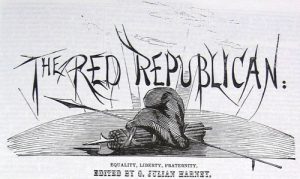

Something entirely missed by biographers of Walt Whitman (1819-92) and poetry scholars generally is how his poetry found its first readership in England. His poem, ‘Resurgemus’, appeared in the 3 August 1850 edition of the Red Republican, a weekly paper of the English Chartists edited in London by George Julian Harney (1817-97).

Harney was a close associate of Karl Marx (1818-83) and Friedrich Engels (1820-95), who as political exiles had moved from Germany to London and Manchester respectively. Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto , first published in German in 1848, was translated by Helen Macfarlane (1818-1861), whose own writings for Harney’s paper were influenced by the German Idealism of GWF Hegel (1770-1831), the Unitarianism of Joseph Priestley (1733–1804) and the Transcendentalism of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882).

The Red Republican was denounced by leading ‘opinion formers’ such as Charles Dickens, Thomas Carlyle and the Times newspaper for its articulation of ‘dangerous’ ideas. The first-ever reaction by the Victorian ruling class to what became known as ‘Marxism’ is to be found in a Times leader of 2 September 1851 entitled ‘Literature For The Poor’. The Times found in the Communist Manifesto an alarming appeal to those people in the lower orders who form a sort of secret society, which is ‘close to our own’ but speaks ‘another language’:

‘… only now and then when some startling fact is bought before us do we entertain even the suspicion that there is a society close to our own, and with which we are in the habits of daily intercourse, of which we are as completely ignorant as if it dwelt in another land, of another language in which we never conversed, which in fact we never saw’.

The Times chose not to name the paper – ‘we are not anxious to give it circulation by naming its writers or the works to which it is composed’ – but did extract some of Helen Macfarlane’s translation of the Communist Manifesto, as serialized in the paper. The selection included this passage as an example of outrageous cheek:

‘Your Middle-class gentry are not satisfied with having the wives and daughters of their Wages-slaves at their disposal, – not to mention the innumerable public prostitutes – but they take a particular pleasure in seducing each other’s wives. Middle-class marriage is in reality a community of wives’.

The Leader, the weekly paper of Christian-socialism and ‘moderate’ Chartism, founded in 1850 by George Henry Lewes and Thornton Leigh Hunt, referred to the writers of Harney’s paper as ‘violent’ and ‘audacious’. Helen Macfarlane, writing under the pseudonym,‘Howard Morton’, responded in a Red Republican article,

‘It has lately been said by the Leader that the writers in the Red Republican are “violent, audacious and wrathfully earnest”… I should think we are. Just about as much in earnest as our precursor, “the Sansculotte Jesus” was when He scourged the usurers and money-lenders, and thimble-rigging stockbrokers of Jerusalem out of that temple they “had made a den of thieves”’.

How then did Whitman’s poetry come to make its first European appearance in Harney’s Red Republican? In 1848, Whitman moved to New Orleans to edit the Crescent newspaper. As there was considerable interest there in the politics of France, Whitman took a deep interest in the Revolution that began in Paris in February 1848 with the overthrow of King Louis Phillipe. The revolutionary tide swept across Europe, overthrowing the despotic monarchies of Austria, Italy, and various German states. But by 1850 the old orders had been restored. According to Jennifer J. Stein,

‘Although the revolutions were fairly quickly squelched, Whitman had gained a taste of the revolutionary spirit. His development from newspaper journalist to democracy-proclaiming poet occurred most dramatically in the years between the mid 1840s and mid 1850s, and although some point to Whitman’s work against slavery as his motivation for becoming freedom’s poetic leader, others point to the revolutions of Europe as his inspiration. In direct response to the revolutions, Whitman wrote “Resurgemus,” a poem printed in the New York Daily Tribune on 21 June 1850… The nature imagery used throughout “Resurgemus” is an important artistic step for Whitman, since he clearly uses it to link the replenishing power of nature to the rejuvenation of revolution and liberation. This poem was among those chosen for inclusion in the first (1855) Leaves of Grass, and it continued to resurface in various forms throughout his later editions.’

‘Resurgemus’, like the Communist Manifesto and the writings of Helen Macfarlane, represented what the Times called ‘another language in which we never conversed, which in fact we never saw’. The New York Tribune was read in London by George Julian Harney, who lifted Whitman’s Resurgemus from its pages and republished it in the Red Republican on 3 August 1850.

Mike Sanders points out that Harney had a ‘continuing desire to raise the literary standard of Chartist poetic production’. To achieve this, Harney rejected a lot of poetry submissions from readers; his reasoning being that bad poetry couldn’t express good politics: ‘Put simply, Chartists argued that the capacity of the working classes both to recognise and produce good poetry demonstrated their fitness for the franchise’. Clearly, Harney regarded Resurgemus as exemplary.

RESURGEMUS.

Suddenly, out of its stale and drowsy air, the air of slaves,

Like lightning Europe le’pt forth,

Sombre, superb and terrible,

As Ahimoth, brother of Death.

God, ‘twas delicious!

That brief, tight, glorious grip

Upon the throats of kings.

Turn back unto this day, and make yourselves afresh. ¶

You liars paid to defile the People,

Mark you now:

Not for numberless agonies, murders, lusts,

For court thieving in its manifold mean forms,

Worming from his simplicity the poor man’s wages;

For many a promise sworn by royal lips

And broken, and laughed at in the breaking;

Then, in their power, not for all these,

Did a blow fall in personal revenge,

Or a hair draggle in blood:

The People scorned the ferocity of kings.

But the sweetness of mercy brewed bitter destruction,

And frightened rulers come back:

Each comes in state, with his train,

Hangman, priest, and tax-gatherer,

Soldier, lawyer, and sycophant;

An appalling procession of locusts,

And the king struts grandly again.

Yet behind all, lo, a Shape

Vague as the night, draped interminably,

Head, front and form, in scarlet folds;

Whose face and eyes none may see,

Out of its robes only this,

The red robes, lifted by the arm,

One finger pointed high over the top,

Like the head of a snake appears.

Meanwhile, corpses lie in new-made graves,

Bloody corpses of young men;

The rope of the gibbet hangs heavily,

The bullets of tyrants are flying,

The creatures of power laugh aloud:

And all these things bear fruits, and they are good.

Those corpses of young men,

Those martyrs that hang from the gibbets,

Those hearts pierced by the grey lead,

Cold and motionless as they seem,

Live elsewhere with undying vitality;

They live in other young men, O, kings,

They live in brothers, again ready to defy you;

They were purified by death,

They were taught and exalted.

Not a grave of those slaughtered ones,

But is growing its seed of freedom,

In its turn to bear seed,

Which the winds shall carry afar and resow,

And the rain nourish.

Not a disembodied spirit

Can the weapon of tyrants let loose,

But it shall stalk invisibly over the earth,

Whispering, counseling, cautioning.

Liberty, let others despair of thee,

But I will never despair of thee:

Is the house shut? Is the master away?

Nevertheless, be ready, be not weary of watching,

He will surely return; his messengers come anon.

WALTER WHITMAN.

References

‘The Revolutions of 1848’, Jennifer J. Stein, in J.R. LeMaster and Donald D. Kummings, eds., Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia (New York: Garland Publishing, 1998).

Mike Sanders, ‘The Poetry of Chartism, Aesthetics, Politics’, History (CUP: 2009), p77.

David Black, Helen Macfarlane: A Feminist, Revolutionary Journalist, and Philosopher in Mid-Nineteenth-Century England. Lexington Books: Lanham, Maryland (2004).

Helen Macfarlane: Red Republican. Essays, articles and her translation of the Communist Manifesto. Edited and annotated by David Black. Unkant Publishers, London 2014.

A.R. Schoyen, The Chartist Challenge: A Portrait of George Julian Harney.

Heinemann: London (1958).