[15 November 2020]

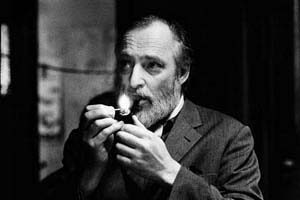

In 1954 the celebrated Danish painter Asger Jorn (1914-73) became aware of, and made contact with, Guy Debrod’s Paris-based Letterist International. Jorn, who had founded the International Movement for an Imaginative Bauhaus in 1953, shared the Letterist International’s hostility to abstract expressionism and socialist realism, and saw their concepts of unitary urbanism and psychogeography as in line with his own critique of functionalist design and architecture.[i]

Debord’s new friendship with Jorn and other leading figures of the artistic avant-garde convinced him that the time had come for the Letterists to shift their focus from the bars of Paris to developments in the wider cultural field of struggle. In an article published in Potlatch in 1957, entitled “One Step Back,” Debord argued that the L.I., rather than constitute itself as an “external opposition,” needed to “seize hold of modern culture in order to use it for our own ends” and join forces with artists – even painters, whose activities has been generally despised by the Letterists. Although Debord accepted that the L.I. might have to initially settle for a minority position within a new international movement, he thought, “all concrete achievements of this movement will naturally lead to its alignment with the most advanced program”:

‘…we need to gather specialists from very varied fields, know the latest autonomous developments in those fields… We thus need to run the risk of regression, but we must also offer, as soon as possible, the means to supersede the contradictions of the present phase through a deepening of our general theory and through conducting experiments whose results are indisputable. Although certain artistic activities might be more notoriously mortally wounded than others, we feel that the hanging of a painting in a gallery is a relic as inevitably uninteresting as a book of poetry. Any use of the current framework of intellectual commerce surrenders ground to intellectual confusionism, and this includes us; but on the the other hand we can do nothing without taking into account from the outset this ephemeral framework.’[ii]

Debord cannily added that the L.I. needed an expansion of its “economic base,” being well aware of the huge amount of money being made out of avant-garde art by the artists themselves as well as the curators and galley-owners. Debord’s potlatch anti-book, Mémoires, published in 1959, featured collages produced in collaboration with, and financed by, Asger Jorn. In July 1957, at a conference in Cosio d’Arroscia, Italy, the Situationist International was founded. Those attending were: Guy Debord and Michèle Bernstein of the Letterist International; Giuseppe Pinot Gallizio, Asger Jorn, Walter Olmo, Piero Simondo, Elena Verrone and Ralph Rumney (Rumney was representing the London Psychogeographical Association, of which he was the sole member). Debord argued in his Report on the Construction of Situations and the Prerequisites for the Organization and Action of the International Situationist Tendency that “the problems of cultural creation can now be solved only in conjunction with a new advance in world revolution.” In order to combat the passive consumption he saw defining spectacular culture, Debord called for the international to organize collectively towards utilizing all of the means of revolutionizing everyday life, “even artistic ones.”

‘We need to construct new ambiances that will be both the products and the instruments of new forms of behavior. To do this, we must from the beginning make practical use of the everyday processes and cultural forms that now exist, while refusing to acknowledge any inherent value they may claim to have… We should not simply refuse modern culture; we must seize it in order to negate it. No one can claim to be a revolutionary intellectual who does not recognize the cultural revolution we are now facing… What ultimately determines whether or not someone is a bourgeois intellectual is neither his social origin nor his knowledge of a culture (such knowledge may be the basis for a critique of that culture or for some creative work within it), but his role in the production of the historically bourgeois forms of culture. Authors of revolutionary political opinions who find themselves praised by bourgeois literary critics should ask themselves what they’ve done wrong.‘[iii]

The S.I.’s later judgment that production of works of art was “anti-situationist,” should be seen in the context of this founding declaration. Although any genuinely experimental attitude, based on critique and supersession of existing conditions, was usable, production of artistic forms was seen as a dead end, leading at best to recuperation and commodification within the spectacle:

‘It must be understood once and for all that something that is only a personal expression within a framework created by others cannot be termed a creation. Creation is not the arrangement of objects and forms, it is the invention of new laws on such arrangement.‘[iv]

Within a few months on the founding of the S.I. in 1957, other groups and individuals from Italy, West Germany and Scandinavia affiliated, thus inaugurating a stormy fifteen-year process of fusions, schisms and expulsions, and an equally stormy spread across the globe of Situationist ideas, which were themselves by no means immune to ideological and cultural “recuperation.” Vincent Kaufman suggests that it would be a mistake to see the exclusions and resignations of the artists (thirty-two in the first four years) as a breakup of, or split in, the S.I.; or as a significant change of direction on Debord’s part:

It was a clarification, a return to a stance that was more coherent, more radical, and certainly closer to that of the defunct Lettrist International… Unitary urbanism survived, but in a politicized form, and developed its critical side, freed of the chimeras, utopias, and models that had characterized it until then. [v]

In the world theorized as the “Society of the Spectacle-Commodity,” Debord and Wolman argued (in 1956) that art could no longer be justified as a “superior activity” or as an honorable “activity of compensation.” In the new conditions of the culture industry only “extremist innovation” was “historically justified.” The “literary and artistic heritage of humanity” could however, still be used for “partisan propaganda” because its artifacts could be deflected or “détourned” from their “intended” purposes.

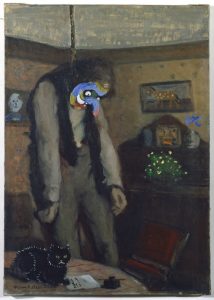

(Asger Jorn, Ainsi s’Ensor (Out of this World – after Ensor), 1962)

Asger Jorn, in an essay entitled “Détourned Painting,” published in the Exhibition Catalogue of the Galerie Rive Gauch, Namur, in May, 1959, wrote,

‘Intended for the general public. Reads effortlessly.

Be modern,

collectors, museums.

If you have old paintings,

do not despair.

Retain your memories

but détourn them

so that they correspond with your era.

Why reject the old

if one can modernize it

with a few strokes of the brush?

This casts a bit of contemporaneity

on your old culture.

Be up to date,

and distinguished

at the same time.

Painting is over.

You might as well finish it off.

Détourn.

Long live painting.’

Jorn then added, in a section entitled “Intended for connoisseurs. Requires limited attention”:

‘The object, reality, or presence takes on value only as an agent of becoming. But it is impossible to establish a future without a past. The future is made through relinquishing or sacrificing the past. He who possesses the past of a phenomenon also possesses the sources of its becoming. Europe will continue to be the source of modern development. Here, the only problem is to know who should have the right to the sacrifices and to the relinquishments of this past, that is, who will inherit the futurist power. I want to rejuvenate European culture. I begin with art. Our past is full of becoming. One needs only to crack open the shells. Détournement is a game born out of the capacity for devalorization. Only he who is able to devalorize can create new values. And only when there is something to devalorize, that is, an already established value, can one engage in devalorization. It is up to us to devalorize or to be devalorized according to our ability to reinvest in our own culture. There remain only two possibilities for us in Europe: to be sacrificed or to sacrifice. It is up to you to choose between the historical monument and the act that merits it.’[vi]

(Asger Jorn – Le Canard Inquiétant, 1959)

Although Asger Jorn’s membership of the Situationist International ended in 1961, when he decided he could not reconcile his working life as an artist with the organizational demands of the International, his financial support for Debord’s work continued until his death in 1973. The concept of détournement, in the hands of practitioners throughout the world, was to give rise to numerous innovations, such as the subversive use of comic books and pirate radio, and the defacing of advertisements with additional images. But detournement was further developed by the Situationists into a more general concept of spontaneous rebellion against the technology of consumption.

(This text has been extracted from David Black’s book, The Philosophical Roots of Anti-Capitalism: Essays on History, Culture and Dialectical Thought, Part Two ‘Critique of the Situationist Dialectic: Art, Class-Consciousness and Reification’, Lexington Books 2013/

[i] Kaufman , Guy Debord, pp. 131-32.00/

[ii] Debord, “One Step Back,” in Guy Debord and the Situationist International: Texts and Documents, (Cambridge: MIT press. 2002), pp. 25-27. Quoted in Vincent, p. 99.

[iii] Debord, “Report on the Construction of Situations” (1957). S.I. Anthology (excerpts), pp.17-25. Reproduced in full at www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/report.html

[iv] Debord, “Report on the Construction of Situations.”

[v] Kaufman, pp. 149-50.

[vi] Asger Jorn, Situationist International Archive Online. www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/painting.html