David Black

11 October 2023

In September 1965 Timothy Leary sent Michael Hollingshead, the Englishman who introduced him to LSD during the Harvard psychedelics project, on a mission. Hollingshead flew into London with 5000 trips of LSD and a list of things to do. Firstly, Hollingshead was to rent the Albert Hall for a psychedelic jamboree with rock bands and poets, with Leary himself hosting the event in his role as the High Priest of LSD. This plan never came off, because of Leary’s bust for marijuana possession in the US at the end of 1965.

Another part of the mission was set up a centre for running LSD sessions and promoting psychedelia in the arts. Hollingshead, with help from old-Etonians, Desmond O’Brien and Joey Mellen, turned a Belgravia flat into the ‘World Psychedelic Centre’. For their LSD sessions, they used the new Leary/Alpert/Metzner book, The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead, as a guide. Hollingshead thought ‘that London would indeed become the centre for a world psychedelic movement’. According to Hollingshead, the World Psychedelic Centre clientele,

…represented perhaps the seminal non-conformism of England’s mid-sixties intelligentsia – not the evangelical non-conformism of such as the Millbrook sect, but an intellectualized form of psychedelic enlightenment, of which popularised Learyism was largely a culmination – that freed so many of England’s educated people from the rigidity of social and class and cultural patterns which had outwardly been solidifying into right-wing Toryism. Their rebellion was typical of this period; the Establishment was the enemy…

One of the reasons Michael Hollingshead gave for coming to London in 1965 was the tendency of the London acid heads – such as those around Alex Trocchi — to politicise, rather than spiritualise, the psychedelic experience. As he put it in The Man Who Turned On the World:

From what I had heard in letters and conversations, the psychedelic movement in England was small and badly informed. It appeared that those who took LSD did so as a consciously defiant anti-authoritarian gesture. The spiritual content of the psychedelic experience was being overlooked.

Hollingshead had been sending shipments of LSD to Trocchi, who distributed it to his contacts in what was to become the London cultural ‘Underground’. Trocchi, born in Glasgow in 1925, had moved to Paris in 1952, where he edited Merlin, an English-language literary magazine. In its pages, Merlin featured contributions from avant-guard writers such as Jean Genet, Eugene Ionesco and Samuel Becket — who, at the time, were unable to get their work published anywhere else in English. Trocchi himself, surrounded by young expatriate American writers, such as Terry Southern and George Plimpton, was, in the words of Greil Marcus, ‘seen as a man of towering literary genius, fated to cut a swath through the world’.

Whatever his differences with Trocchi, Hollingshead certainly arrived in London at the right time for a ‘revolution in consciousness’. As Charles Radcliffe wrote in his memoirs:

“The possibility of real change no longer seemed remote. Towards the end of 1965, there was a definite, almost tangible quickening of the generational pulse, ever widening interests and excitement in myself and everyone I knew. Every day there were more of us to know… Many former ‘politicos’ sensed that ‘politics’ wasn’t over but was simply one of many items on the burner. More and more people were talking about LSD, the mind-expanding drug lysergic acid diethylamide 25 [as]… a serious inward voyage of discovery, not to be taken lightly… LSD was legal but for how long? And how could I get some?”

(Charles Radcliffe, Don’t Start Me Talking: Subculture, Situationism and the Sixties)

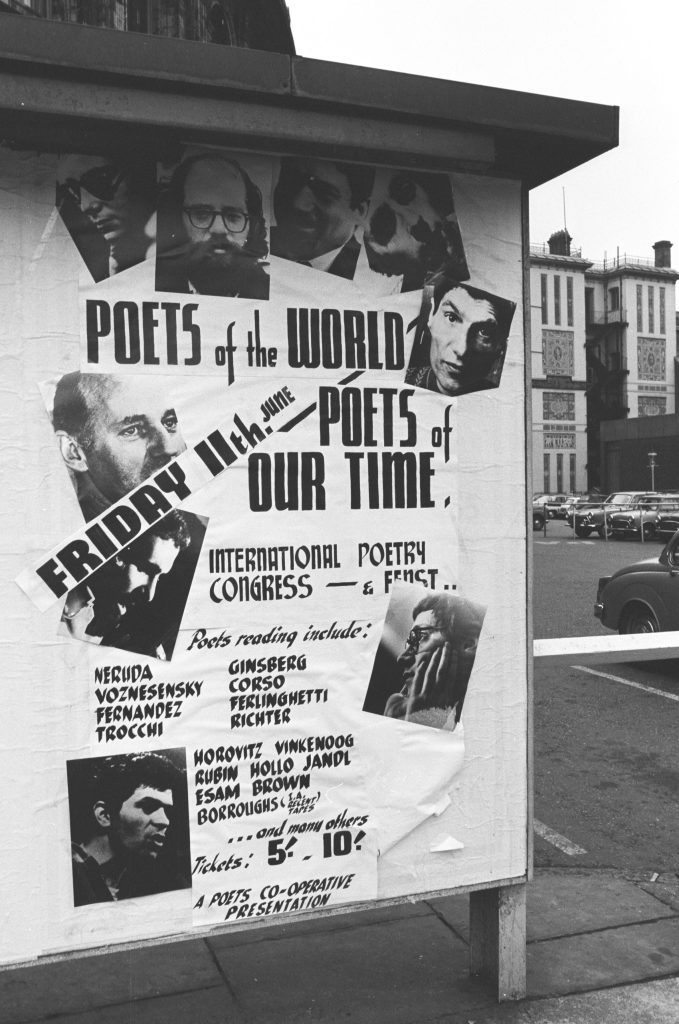

The British Underground achieved critical mass in June 1965 with the International Poetry Congress at Albert Hall, which drew 5,000 people. The event was hosted by Alex Trocchi who, having been expelled by Guy Debord from Situationist International, had launched a project called Sigma, which aimed to build

‘a new decentralised organisation of writers, painters, sculptors, musicians, dancers, physicists, bio-chemists, philosophers, neurologists, engineers, and whatnots, of every race and nationality’.

To co-oordinate a ‘catalogue of such a reservoir of talent, intelligence and power’ would be ‘of itself a spur to our imagination’. For London he planned to found a

‘living-gallery-workshop-auditorium-happening situation where conferences and encounters are to be undertaken… It will be our window on the metropolis, a sigma-centre… an experimental situation in which what is happening cannot be described in terms of conventional categories (which it transcends)… Certain hallucinatory properties of drugs make them central and urgently relevant to any imaginable enquiry into the mystery of the human mind. Unfortunately, ignorance, hysteria and sensationalism have contributed to making this largely a police matter’.

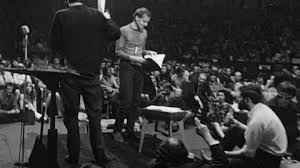

Trocchi believed that psychiatrist RD Laing’s ideas on the usefulness of LSD in treating schizophrenia were ‘entirely in line with those proposed by Sigma’. Trocchi planned to produce a book titled ‘Drugs of the Mind’ with Laing and Willam Burroughs; but like so many of Trocchi’s projects, it was never carried through. This was partly because Trocchi was distracted by his heroin habit, and proved incapable of keeping Sigma’s finances separate from his own. In 1965, Trocchi did, however. pull off the Albert Hall readings, which gave birth to the term, ‘Underground’. The event was filmed by Peter Whitehead, who entitled his 33-minute documentary Wholly Communion. It featured, in order of appearance (all men; such were the times): Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael Horovitz, Gregory Corso, Harry Fainlight, Adrian Mitchell, Christopher Logue, Alexander Trocchi, Ernst Jandl, and Allen Ginsberg. It can be seen on YouTube HERE

See David Black, Psychedelic Tricksters: A True Secret History of LSD (London: 2022]