By David Black

9 August 2022

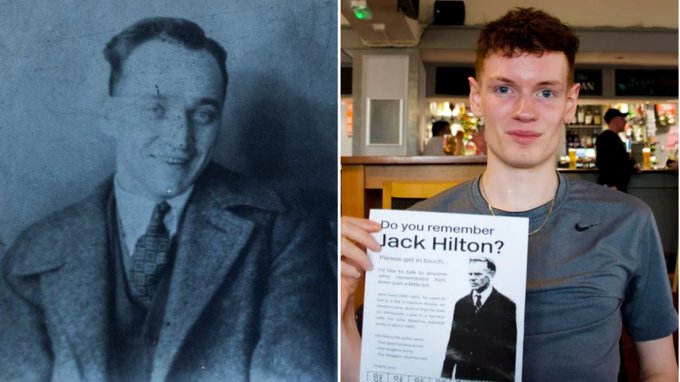

Rochdale’s Jack Hilton (1900-83) was hailed in the 1930s as a great novelist by George Orwell and WH Auden, but died modestly and unacclaimed. For 80 years his novels have been virtually impossible to get hold of after they went out of print, the ownership of the publishing rights being unknown. Now, Hilton’s works are getting back into print, thanks to the literary detective work of Jack Chadwick, a 28-year-old bartender and aspiring writer who discovered Caliban Shrieks while visiting Salford’s Working Class Movement Library last year.

“Caliban Shrieks has this unique quality that I hadn’t come across before and I found it so compelling,” Chadwick told the Independent.

“It’s so raw, it feels like it’s coming to you from across the pub table.”

As BPC couldn’t find George Orwell’s review of Caliban Shrieks online, we did a paper-search and transcribed it.

Adelphi magazine, March 1935.

Caliban Shrieks by Jack Hilton

Reviewed by George Orwell

This witty and unusual book may be described as an autobiography without narrative. Mr Hilton lets us know, briefly and in passing, that he is a cotton operative who has been in and out of work for years past, that he served in France during the latter part of the war, and that he has also been on the road, been in prison, etc etc; but he wastes little time in explanations and none in description. In effect his book is a series of comments on life as it appears when one’s income is two pounds a week or less. Here, for instance, is Mr Hilton’s account of his own marriage:

Despite the obvious recognition of marriage’s disabilities, the bally thing took place. With it came, not the entrancing mysteries of the bedroom, nor the passionate soul-stirring of two sugar-candied Darby and Joans, but the practised resolve that, come what may, be the furnishers’ dues met or no, the rent paid or spent, we – the wife and I – would commemorate our marriage by having, every Sunday morn, ham and eggs, So it was we got one over on the poet, with his madness of love, the little dove birds, etc.

There are obvious disadvantages in this manner of writing — in particular, it assumes a width of experience which many readers would not possess. On the other hand, the book has a quality which the objective, descriptive kind of book almost invariably misses. It deals with its subject from the inside, and consequently it gives one, instead of a catalogue of facts relating to poverty, a vivid notion of what it feels like to be poor. All the time that one reads one seems to hear Mr Hilton’s voice, and what is more, one seems to hear the voices of the innumerable industrial workers whom he typifies. The humorous courage, the fearful realism and the utter imperviousness to middle-class ideals, which characterise the best type of industrial worker, are all implicit in Mr Hilton’s way of talking. This is one of those books that succeed in conveying a frame of mind, and that takes more doing than the’ mere telling of a story.

Books like this, which come from genuine workers and present a genuinely working-class outlook, are exceedingly rare and correspondingly important. They are the voices of a normally silent multitude. All over England, in every industrial town, there are men by scores of thousands whose attitude to life, if only they could express it, would be very much what Mr Hilton’s is. If all of them could get their thoughts on to paper they would change the whole consciousness of our race. Some of them try to do so, of course; but in almost every case, inevitably, what a mess they make of it! I knew a tramp once who was writing his autobiography. He was quite young, but he had had a most interesting life which included, among other things, a jail-escape in America, and he could talk about it entrancingly. But as soon as he took a pen in his hand he became not only boring beyond measure but utterly unintelligible. His prose style was modelled upon Peg’s Paper (“With a wild cry I sank in a stricken heap” etc), and his ineptitude with words was so great that after wading through two pages of laboured description you could not even be certain what he was attempting to describe. Looking back upon that autobiography and number of similar documents that I have seen, I realise what a considerable literary gift must have gone into the making of Mr Hilton’s book.

As to the sociological information that Mr Hilton provides, I have only one fault to find. He has evidently not been in the Casual Ward since the years just after the war, and he seems to have been taken in by the lie, widely published during the last few years, to the effect that casual paupers are now given a “warm meal” at midday. I could a tale unfold about those “warm meals”. Otherwise, all his facts are entirely accurate so far as I am able to judge, and his remarks on prison life, delivered with an extraordinary absence of malice, are some of the most interesting that I have read.

#