David Black

21 July 2023

On 30 March 1850, Charles Dickens, having established himself as Britain’s most popular novelist, launched Household Words: A Weekly Journal. In an editorial, headed ‘A Preliminary Word’, he promised his readers that: ‘No mere utilitarian spirit, no iron binding of the mind to grim realities, will give a harsh tone to our Household Words‘.

At this time there was, however, one potential rival he hoped his paper would ‘displace’:

‘Some tillers of the field into which we now come, have been before us, and some are here whose high usefulness we readily acknowledge, and whose company it is an honour to join. But, there are others here – Bastards of the Mountain, bedraggled fringe on the Red Cap, Panders to the basest passions of the lowest natures – whose existence is a national reproach. And these, we should consider it our highest service to displace.’

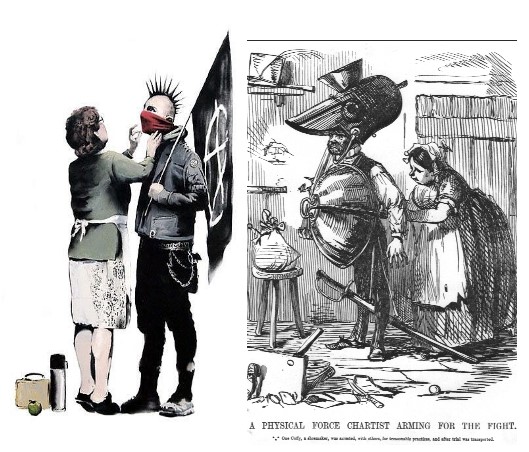

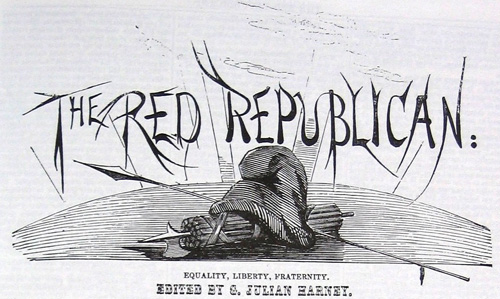

Although he didn’t care to name it, there is no doubt that he was referring to the Red Republican, a Chartist weekly, edited by George Julian Harney. Dickens’ attack did not go unnoticed by the Red’s most prolific contributor: Helen Macfarlane, Scottish anti-slavery campaigner, feminist, socialist Christian, Hegelian philosopher and friend of Karl Marx.

What Helen Macfarlane thought of Dickens’s fiction is not known, but she certainly didn’t like his politics (or lack of) as can be seem from the following.

‘The Red Flag in 1850’, Red Republican, 13 July 1850:

We, the English Socialist-democrats, may be “the ragged fringe on the Red Republican cap, the bastard of the Mountain” as the sapient Mr. Boz has been pleased to denominate us, but we are something more than that. Chartism and Red Republicanism must henceforward be considered as synonymous terms… And what is Chartism? … it would appear that Chartism is something very much resembling the hope and aspiration of a majority of the working men of England’.

‘Fine Words (Household or Otherwise) Butter No Parsnips’, Red Republican, 20 July 1850):

The above moral reflection occurred to me on reading an article in the last monthly edition of Dickens’ Household Words, wherein two poor little starving children, who stole a loaf of bread, and were sentenced by a Bow-street magistrate, (“a Daniel come to judgment”) to be whipped for this “awful crime against society, property, and order”. Further, the writer relates divers particulars concerning the ragged schools in Westminster, tending to show that persons belonging to the offscourings of society—persons who, from their infancy, had been brought up in every kind of vice, are reclaimable with a little trouble, but that the first condition of that reformation is to give them the means of earning their living in an honest way. In the cases mentioned by this writer [Dickens], this was done by sending the subjects of the experiment to Australia, where, by last accounts, they “were doing well”.

I daresay they “were doing well”, in a country where the poor are not altogether thrust from the banquet of life by the rich; where the land, the common gift of God to all mankind, is not altogether monopolized by one land-owning class; where the honest man who only has his strength and skill to aid him in the struggle for existence, does not altogether become the prey of bourgeois profit-mongers, whose grand problem is—to get a maximum of work done for a minimum of wages. No doubt, any one, willing to work, would “do well” in a place like this. The remedy proposed by the above writer for the state of things he describes is—National Education! “If a son asks bread from any of you that is a father, will he give him a stone?”A spelling-book as a cure for hunger, was an amount of humanabsurdity, which evidently had not crossed the imagination of the Nazarean Teacher. Words are the panacea of the Whig Quacks and rosewater political sentimentalists of the Boz school. Education will do much, and a fit subject for its beneficent influences would have been the brutal, well-fed Dogberry who sentenced these starving children to be whipped; but Education will not satisfy the animal wants of man; the rule of three will not feed the hungry, or the Penny Magazine clothe the naked. How are the people of this country to be fed? That is the question. Not, how are the starving, homeless, hopeless wretches, dying by inches of cold and hunger, to be taught “reading, writing and arithmetic”. Your lessons in morality will do much for men who must either starve or steal, for women who must go on the streets and drive a hideous traffic in their own bodies, to get a meal for their starving children! Rose-coloured political sentimentalists!…

Transport the lazy drones who eat up the honey; transport the landowners and the thimble-riggers of the Stock Exchange, and there would be bread enough and room enough then, for all “our surplus population”. How are the people of this country to be fed? That is the problem for solution. The Protectionists did not solve it. The Free-traders are not solving it. Rosewater, self-sawdering, sentimental Whigs talk of National Education. Meanwhile, the producers die of inches of hunger—pauperism, and its attendant—crime—are on the increase. The condition of “moral England, the envy of surrounding nations”, is in a fair way of becoming very unenviable under the Upas-tree of a “glorious British Constitution and time-honoured Institutions of our ancestors”. It is well Time honours them, for I think nobody else does, and time must be in his dotage if he does anything of the kind.

In our own times, when charity has become an industry and, all too often, a racket serving the interests of the rich and powerful, Helen Macfarlane’s contempt for it still hits the spot:

‘The Democratic and Social Republic’, Red Republican, 12 October 1850)

We feel humiliated and pained when a beggar stretches out his hand to us for “charity”—that insult and indignity offered to human nature; that word invented by tyrants and slavedrivers—an infamous word, which we desire to see erased from the language of every civilised people… We believe, that unless God be a fiction, justice a chimera, truth a lie—it is possible to find social arrangements in virtue of which all the inhabitants of a given country could obtain a fair share, not only of the necessities, but of the comforts and luxuries of life—in exchange for the honest labour oftheir own hands… That is our dream, that is our Utopia; it is the democratic and social republic.’

A Sign in The Times

Dickens’s anathema against the Red Republican was echoed in a Times leader of 2 September 1851 entitled ‘Literature For The Poor’. Like Dickens, the Times chose not to name the paper – ‘we are not anxious to give it circulation by naming its writers or the works to which it is composed’ – but did extract some of Helen Macfarlane’s translation of the Communist Manifesto, as serialized in the paper. The selection included this passage as an example of outrageous cheek:

‘Your Middle-class gentry are not satisfied with having the wives and daughters of their Wages-slaves at their disposal, – not to mention the innumerable public prostitutes – but they take a particular pleasure in seducing each other’s wives. Middle-class marriage is in reality a community of wives’.

The Times found in the Communist Manifesto an alarming appeal to those people in the lower orders who form a sort of secret society, which is ‘close to our own’ but speaks ‘another language’:

‘… only now and then when some startling fact is bought before us do we entertain even the suspicion that there is a society close to our own, and with which we are in the habits of daily intercourse, of which we are as completely ignorant as if it dwelt in another land, of another language in which we never conversed, which in fact we never saw’.

(In 2014, I edited Red Republican: The Complete Annotated Works of Helen Macfarlane, for Unkant (Britain’s most radical publisher of that time, which unfortunately went out of business a couple of years later). It needs to be republished in a new edition.)