2 December 2023. Over the next month or so I’ll be serialising a chapter from Psychedelic Tricksters: A True Secret History of LSD. (Amazon. Also on Kindle: HERE), published in 2022. For this chapter I am especially indebted to Tim Scully’s extensive and generous correspondence with me between September 2019 and May 2020. – D.B.

Chapter Six – The New Prohibition in the USA versus the Acid Underground

‘To live is to be hunted.’ Philip K Dick, Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said

Psychedelic Alchemy

Between the early 1960s and early 1970s at least 10 million Americans took LSD. They were supplied by scores of underground LSD laboratories, which sprouted up in various parts of the United States between 1963 and 1973. About fifty of these labs are known about; some of them were in operation for just a few months, others for years. Apart from the ‘known’ labs (which are usually only known about because of prosecutions), there must have been many others, which made large quantities of LSD, but were never discovered. For the purposes of this book I would emphasize that the LSD chemists who feature in the following pages by no means produced most of LSD in the USA; they were just the ones unfortunate enough to become ‘famous’ (or ‘infamous) for their work. As a general rule, manufacturers of illegal substances, not wanting to end up in court, avoid publicity. One of them in particular, achieved ‘legendary’ status as ‘Mr LSD’ without ever wanting it.

He was born August Owsley Stanley III (1935-2011), grandson of a US senator from Kentucky, and is more commonly known as ‘Owsley’, or to his friends, as ‘Bear Stanley’. In 1964 Owsley took LSD for the first time in the form of a somewhat impure green goo, made by Douglas George, an amateur chemist who distributed it free in Berkeley. Later that same year, Owsley tried a full-dose Sandoz LSD capsule and was so impressed that he sought out all of the published material he could find on LSD manufacture.

Owsley studied a book on alchemy, entitled The Kybalion. Published in 1908, its authors (the pseudonymous ‘Three Initiates’) claimed it was based on the teachings of Hermes Trismegistus, the semi-mythical Egyptian (some say Greek) sage. What impressed Owsley was the book’s thesis that the alchemic ‘transformation of substances’ was purely allegorical. In Owsley’s interpretation, ‘The lead and the gold is the lead of the primitive nature into the gold of the enlightened man. Alchemy didn’t talk about lead into gold until it had to deal with the church in the early Middle Ages’. The Kybalion ‘was perfect because it put into total context all the things I had experienced on acid. The universe is a creation entirely within a being that is outside time and space, and dreaming what we are. Everything is connected, because it’s all being created by this one consciousness. And we are tiny reflections of the mind that is creating the universe. That’s what alchemy says’.

Between the years of 1950 and 1965, over 1,000 scientific papers on the potential therapeutic effects of LSD and other hallucinogens were turned out by researchers. During the same period some 40,000 patients were treated with LSD therapy as treatment for mental illnesses. But in 1962, the U.S. Congress passed new drug safety regulations and the Food and Drug Administration began to clamp down on research into the effects of LSD as well as its manufacture and distribution. Owsley however, was not deterred. In the winter of 1964 Owsley bought 40 grams of lysergic acid from the Sigma chemical company and made his first batch of LSD at the Green Factory in Berkeley. In February 1965 the Green Factory was raided by the authorities and Owsley Stanley moved his lab equipment to the basement of a friend’s house in Los Angeles.

So far, Owsley’s LSD hadn’t been pure enough to crystallize, but he soon solved this problem by mastering chromatography – a technique for separating out a mixture of chemicals. With his partner, Melissa Cargill, he set up another LSD lab at a rented a house on Lafler Road, Los Angeles, near California State University. He bought lysergic acid from the Cyclo chemical company and made several grams of pure crystalline LSD amounting to at least 30,000 doses. These were put into gelatin capsules and sold by mail order. The method of putting LSD into capsules had its drawbacks. It was difficult to get equal-sized doses into the capsules because they had to be filled by pressing the dry powder into them on a flat surface, such as a mirror; but the amount of powder that got into each capsule could vary significantly, depending on how the pressing was done. Also, unscrupulous wholesalers could remove the content of the capsule, dilute or counterfeit it, and put it into a larger number of capsules.

Owsley, in his determination to market a standard dose of 300 μg (micrograms) with a solid promise of purity, switched from capsules to tablets, which were far more accurate and consistent in dose size. Owsley obtained triturate boards to produce uniform dose sizes in a tablet form which would be very difficult to counterfeit. There remained however, the problem that in the final drying process the active ingredient in the moisture tended to migrate to the surface of the tablet, where it could be undermined by sweat from handling or exposure to UV light. He solved this problem by dispersing the LSD content in tribasic calcium phosphate, a chemical which could adhere itself to the LSD strongly enough to prevent any migration to the surface of the tablet during the evaporation of the solvent. The phosphate accounted for 10 per cent of the total weight of the tablet; the remaining 90 per cent was made up with lactose.

The Los Angeles drug squad soon learned about Owsley Stanley’s activities after he sold a gram of LSD to the guitarist, Perry Lederman. After Lederman told everyone he sold it to that Owsley Stanley had made it, the drug squad put Owsley under surveillance. They went through his trash, where they found letters from his mail-order customers, and also obtained copies of his orders for lysergic acid from the Cyclo company. Owsley and the Grateful Dead On December 11th, 1965, Owsley attended a Grateful Dead ‘Acid Test’ gig at Muir Beach, Marin County. Tripping heavily, he found the Dead to be ‘magic personified’, and ‘the most amazing group ever’. On January 29, Owsley attended another Dead performance and Acid Test at Sound City, a San Francisco radio studio. The band members, impressed by Owsley’s enthusiasm and resourcefulness, suggested he become their manager. Owsley insisted he would be of more use as their sound engineer. The Dead, like most other rock bands of the time, were using equipment which made unwanted noises and produced a poorly balanced overall sound. After the Dead took up his offer, Owsley introduced state-of-the art equipment such as high-quality cables and connections which minimized hum and hiss from the instruments, and big hi-fi ‘Voice of the Theater’ speakers for the PA system. At the Sound City Acid Test Owsley, having met Tim Scully a few weeks earlier, offered him and his friend Don Douglas a chance to travel with him and the Grateful Dead to Los Angeles and work with him doing electronics and roadie work for the band.

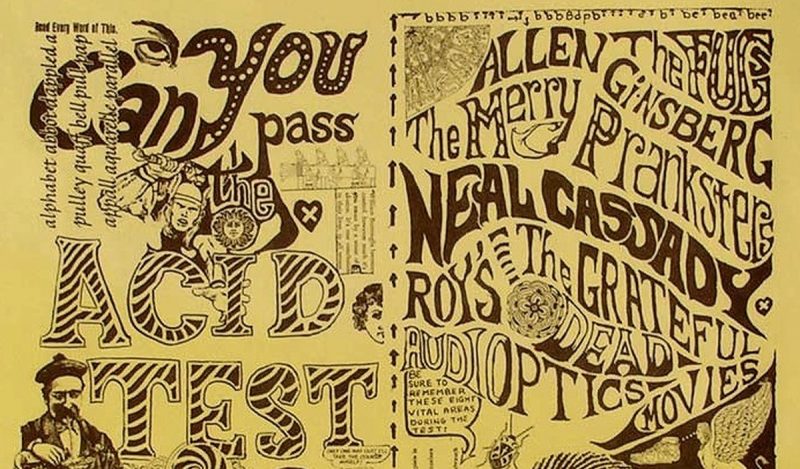

Owsley had experience of engineering in radio and television, but he didn’t have enough knowledge of electronic circuit design to implement his ideas for customised equipment. Scully had the technical know-how; and he also wanted to make LSD with Owsley. Scully, born 1944 in Berkeley, California, had studied math and physics at the University of California until 1963. From 1963 to 1965 he was employed by Atomic Laboratories Inc. as an electronics design consultant. In 1965 he took evening classes at University of California in advanced calculus and atomic physics. On April 15, 1965, he took LSD for the first time. In late-1965 advertisements began to appear in California posing the question, ‘Can you pass the acid test?’ Properly defined, the ‘Acid Tests’, were events with music played by the Grateful Dead, LSD supplied by Owsley, organized by the Merry Pranksters, a group of Californian pagans gathered together by Ken Kesey, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion.

Kesey and the Pranksters traversed the country in an old school bus, repainted in psychedelic colours with the words, ‘Caution! Weird Load’, inscribed on the back. Neal Cassady, former road-buddy of Jack Kerouac, went along as driver. The Pranksters’ stated mission was to re-experience America as a ‘trip’ and to ‘prank’ its citizens out of their conformist conditioning by means of noisy, rude, but colourful behaviour and LSD tripping. As it turned out, even non-conformists, like the Millbrook community in Poughkeepsie found the Pranksters too wild; especially after Kesey ‘adopted’ a chapter of the Hell’s Angels as his bus-escort. According to Richard Alpert, when the Pranksters’ visited Millbrook it felt like being in ‘a pastoral Indian village invaded by a whooping cowboy band of Wild West saloon carousers’. The Pranksters’ events featured Owsley’s acid disguised as a vat of Orange Kool-Aid bearing the warning label, ‘Electric’. Owsley had serious doubts about what the Pranksters were up to. He thought the Pranksters’ practice of ‘Magic’ had its dangers:

‘Kesey was playing with something he did not understand. I said to him, “You guys are fucking around with something that people have known about forever. It’s sometimes called witchcraft, and it’s extremely dangerous. You’re dealing with part of the unconscious mind that they used to define as angels and devils. You have to be very careful, because there are all these warnings. All the occult literature about ceremonial magic warns about being very careful when you start exploring these areas in the mind.” And they laughed at me’.

Tim Scully, in a memoir of his time with Owsley and the Grateful Dead, describes one of the early Acid-Tests in California:

‘Everyone paid admission: all the people in the acid test, all the members of the Grateful Dead, and anyone who was seduced off the street. It was all very democratic. And also potentially problematic. At the Watts acid test, for example, folks who had never heard of LSD came in, drank some Kool-Aid, and started getting high. If you were surrounded by strobe lights, with Pranksters doing things with their sound systems – all designed to disorient –the experience could be really fun, if that’s what youwere into. But it could be terrifying if you didn’t knowwhat to expect’.

Scully installed transformers to reduce the impedance of the signals being transmitted through long cables, which otherwise picked up excessive 60 cycle hum from nearby power lines. He designed and built a mixing desk to receive the modified signals and output them into both the PA and the tape recorder. From January to July 1966 Scully lived and worked with Grateful Dead and their entourage, designing and installing numerous other technical innovations as well as taking on roadie responsibilities. In March 1966 in Los Angeles a group of hippies were sitting in a Cantor’s cafe known as ‘Capsule Corner’, amiably chatting to photo-journalist Lawrence Schiller of Life magazine, who was working with correspondent Gerald Moore for an article on the new hippie sub-culture. The mood darkened however, when a young woman came in brandishing a peanut jar full of LSD tablets and triumphantly announced, ‘Look what I just bought from Owsley’. Bob Hamilton, a friend of Scully’s, rushed to a phone-box and called Owsley, telling him he should clean up his premises. On March 25 1966, Life’s front cover appeared with headline, ‘The Exploding Effect of the Mind Drug that got Out of Control: LSD’. The coverage in Life set off a hysterical reaction in the rest of the media.

By the end of July 1966, Owsley (now calling himself ‘Bear Stanley’) had run out of both money and LSD. He decided to set up another lab. But he had earlier agreed with the Grateful Dead that he would not work in a lab while traveling or living with them. Also, by then the band had reluctantly decided that the new improved electronic gear he had supplied them with had become a ‘logistical nightmare’ in terms of setting up and dismantling at every gig. Owsley sold the new equipment, bought the band new Fender amps and speakers, and then went off to work in his lab in Point Richmond.

Next up: (continuing this chapter) Owsley feels the heat and withdraws from LSD production and withdraws. His apprentice, Tim Scully, goes underground, Nick Sand moves west and teams up with him.