(27 November 2020)

(27 November 2020)

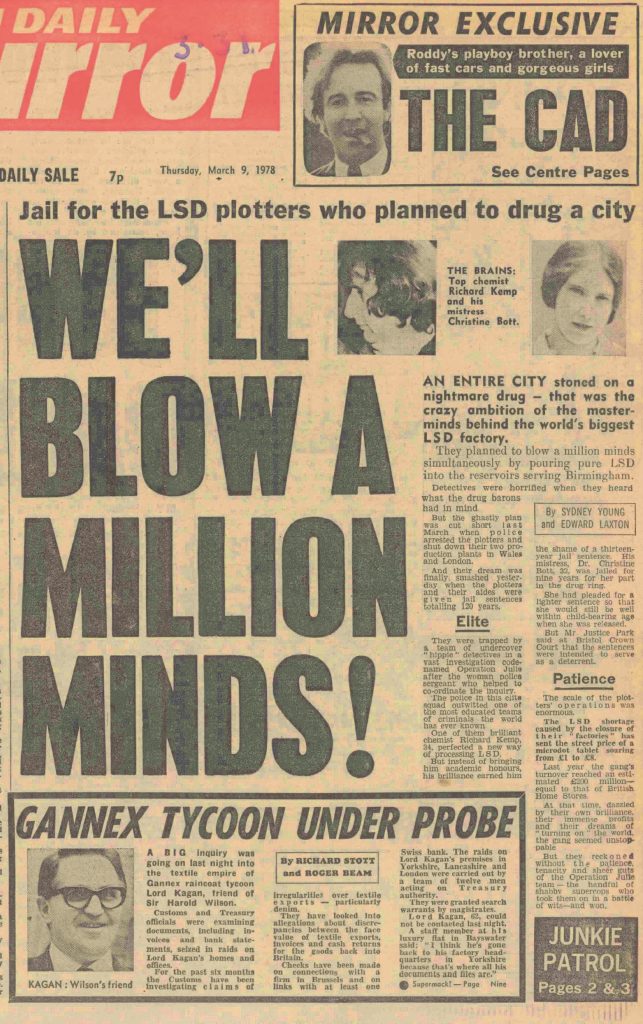

To commemorate the hundreth anniversary of Timothy Leary’s birth we present an extract from David Black’s Psychedelic Tricksters: A True Secret History of LSD: sections 3 to 5 of Chapter 10 – ‘Timothy Leary’s Reality Tunnels: One Escape After Another‘.

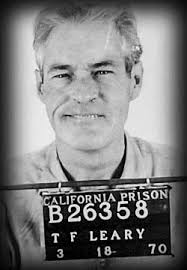

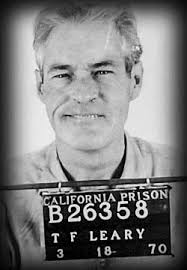

Timothy Leary’s Armed Love

In January 1970 an Orange County judge handed Tim Leary a ludicrous sentence totalling 20 years for two minor marijuana offences. As Leary’s friends organised a defence campaign, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love paid the Weather Underground $25,000 to free him; a task made much easier by his transfer from Fulsom Prison to the minimum security establishment at San Luis Obispo. In September 1970, Leary, according to his own account, took his life in his hands and climbed along forty yards of telephone cable which ran twenty feet-high from the prison roof to a telegraph pole on the outside. Leary was picked up on a nearby highway by Clayton Van Lydegraf, a former First Lieutenant pilot in World War Two and a veteran Stalinist. Van Lydegraf, who never had any time for the hippie counterculture or LSD, told Leary, ‘I was against this whole thing from the start. If it were up to me you’d still be rotting in jail’.[i] Presumably, Van Lydegraf was given the job of getaway driver, precisely because he didn’t look or talk like a hippie. After few changes of cars and drivers Leary was taken to meet up with the group’s leaders, Bernadine Dohrn, Bill Ayers and Mark Rudd. The success of this first part of the mission was celebrated with an LSD tripping session.

The second part of the operation was to spirit Leary and his wife, Rosemary out of the US and send them to Algiers and hook up with Eldridge Cleaver, an exiled leader of the Black Panther Party. The FLN government in Algiers was at the time hospitable to an array of revolutionary exiles from across the world. Leary had always been anti-racist, but had never, until now, identified with revolutionary politics, especially that which embraced armed-struggle. What had changed him in San Luis Obispo prison? One factor was the influence of his wife, Rosemary, who much more than Tim, was a ‘natural’ radical and well connected with the more ‘extreme’ elements of American leftism. When planning to spring Tim from his prison she got him to approve the use of firearms by the rescue team that was being assembled. Another factor was the constant supply of LSD smuggled into prison by Rosemary. According to biographer John Higgs,

‘By using LSD in prison he imprinted a new reality, and replaced his old beliefs with an outlook that made him better adapted to survive in his new environment… Tim had spent years talking about reprogramming the mind in just this way, yet when he did what he had described, his audience was bewildered… Tim had simply, to use his own jargon, rebuilt his “reality tunnel”’.[ii]

Leary, facing decades behind bars, had come to believe that Rosemary and the revolutionaries were his only hope for freedom. Therefore his natural pacifism was put into suspension for the duration. Like any actor playing the good guy, Leary’s had a mission to fulfil in the cosmic drama: to promote solidarity and co-operation between the hippie counterculture and the Black Revolution.

When Leary appeared to buy the Weather Underground’s skyed-out politics, issuing a statement from hiding that, ‘To shoot a genocidal robot policeman in defence of life is a sacred act,’ he alienated many of his old friends. Ken Kesey, the old Electric-Koolaid-Acid-Tester, published an open letter in response which pleaded more in sorrow than in anger: ‘Oh my good doctor, we don’t need one more nut with a gun’.[iii]

Leary however, was playing revolution politics as a game. This is clear from an interview he did with Paul Krasner twenty years later:

‘Krasner: ..when you escaped from prison, you said, “Arm yourselves and shoot to live. To shoot a genocidal robot policeman in defence of life is a sacred act”

Leary: Yeah! I also said “I’m armed and dangerous.” I got that directly from Angela Davis. I thought it was funny to say that.

Krasner: I thought it was the party line from the Weather Underround.

Leary: Well, yeah. I had a lot of arguments with Bernadine Dohrn,

Krasner: They had their own rhetoric. She even praised Charles Manson.

Leary: The Weather Underground were amusing, They were brilliant, Jewish, Chicago kids. They had class and dash and flash and smash. Bernadine was praising Manson for sticking a fork in a victim’s stomach. She was just being naughty’. [iv]

With fake passports, Leary and his wife, Rosemary, slipped out of America in disguise and flew to Algeria to meet Eldridge Cleaver. Cleaver had joined the Black Panther Party after serving an eight year sentence in San Quentin prison for rape and attempted murder. Released in 1966, Cleaver became a journalist for Ramparts and served as Minister of Information of the Black Panther Party. In 1968 he led an ambush of Oakland police officers in which two officers were wounded and 17-year-old Panther Bobby Hutton was shot to death by police after surrendering. Cleaver fled to Cuba, where he was at first welcomed by the communist authorities. However, when he was joined by Clinton Smith and Byron Booth, who had hijacked a plane from California to Cuba, the hospitality cooled. Fidel Castro, not wanting his island to become a haven for plane-hijackers with dubious (possibly CIA) connections, packed the three of them off to Algeria. As other Black Panther exiles began to congregate in Algiers, Cleaver asked the FLN government of Algeria to provide the US Black Panthers with an ’embassy’. This request was granted shortly before the Learys’ arrival there.

Cleaver was impressed by Nixon’s naming of Leary as ‘the most dangerous man in America’. Leary describes his first meeting with Cleaver at a villa in Algiers, which had been provided by the FLN government:

‘Eldridge greeted us warmly at the gate, recognising that our presence meant more cards in his hand. As Rosemary and I sat uneasily in the haute bourgeois French-provincial living room, Cleaver laid out his plan. He would obtain political asylum for us from the Algerians. Then we’d set up an American government in exile. The Algerians had already recognized the Panthers as the American Liberation Front and ultimately we could swing the entire Third World behind our cause. I suggested that we could represent the non-political counter-culture forces of America. We’d invite dissident groups, draft resisters, anti-war activists, hippies, Weathermen, rock stars, beatniks, bohemians, poets. I agreed that we should form a highly visible, alternative government to the Nixon regime. There was no question that, if we could get a base operating, many counter-culture people would come by to visit. The most effective tactic would be to operate a media centre. If the Algerians will let us set up broadcast facilities, we can start a Radio Free America that would beam over to Europe and the armed forces bases. We could win the respect of the youth and the liberals and the anti-war people in Europe… [for] a popular front of the large majority of Americans who want a peaceful friendly prosperous world’. [v]

Leary’s sentiments were received politely but with sceptical bemusement. Cleaver saw no future for any kind popular front, least of all one composed of the people Leary had in mind. When Leary began receiving visitors – old friends, revolutionary tourists, psychedelic pilgrims and journalists – Cleaver complained that the journalists tended to relegate the Panthers’ revolutionary politics to the colourful backdrop of the story of Leary’s prison escape.[vi] Anita Hoffman of the Yippies recalled,

‘…I revolted against Cleaver’s dictatorial rule, but was surprised to find I had no allies among the obedient lefties I was travelling with. So I escaped by climbing out of window and talking my way out at customs at the airport. Since the Panthers were guests of the Algerians, the Algerians wanted the Panthers’ approval to let me leave. But at that point they didn’t know I was gone’.[vii]

Cleaver assured the Algerian government that he could control Leary’s drug use and bouts of ‘nonsensical political eloquence’. First, Cleaver got Leary to participate in a film shooting session for the Panthers aimed at a US audience. Cleaver wanted Leary to publicly renounce drugs as a distraction from building armed resistance to US imperialism. Leary was diplomatic rather than apologetic:

‘If taking any drug postpones for ten minutes the revolution, the liberation of our sisters and brothers, our comrades, then taking drugs must be postponed for ten minutes … However, if one hundred FBI agents agreed to take LSD, thirty would certainly drop out’.[viii]

Leary was still committed to fulfilling his promises to the Weather Underground. Now that the escape from prison and flight into exile had been accomplished, it was time for the third part of the mission: to organise a tripping session with Eldridge Cleaver, in the hope that he would became less insular and sectarian; and embrace unity between Black Revolutionaries and hippie radicals such the Weather Underground. Cleaver had actually tripped on LSD with Yippie leaders Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman in Berkeley back in 1968. They had failed to change Cleaver’s thinking, but Leary thought it was still worth trying to do so. As he had a good supply of LSD smuggled to him in Algiers, he suggested to Cleaver that they trip together, and Cleaver agreed. The session however, simply aggravated Cleaver’s paranoia, and plunged him into a mood of pessimism.

Cleaver, wishing to assure the Algerian government that he was hosting a real anti-imperialist revolutionary, rather than a white American drugs fiend, sent Leary on a Panther-led delegation to the PLO training camps in the Levant. The delegation consisted of Leary, Donald Cox of the Black Panther party, Panther fundraiser Martin Kenner, and Bernadine Dohrn’s sister, Jennifer , who represented a sort of ‘political wing’ of the Weather Underground. The idea was to have Leary appear before the world media at a PLO camp in Jordan alongside Fatah guerrillas, Black Panthers and white American sympathisers. However, when they arrived in Beirut via Cairo they found themselves besieged at their hotel and followed everywhere by the Western press, who had been tipped off about their arrival. The plan to visit Fatah training camps in Jordan and Syria had to be abandoned when the Lebanese government, under US diplomatic pressure, sent a police squad to escort them to the airport.

Leary and party returned to Cairo. In Cairo, according to Cleaver’s then collaborator Elaine Mokhtefi, Leary became ‘paranoid and hysterical… uncontrollable… scaling walls, hiding behind buildings, raising his arms and screaming in the streets’. The Algerian ambassador to Egypt put them on a plane back to Algiers. On their return Leary and Rosemary began partying with LSD at the desert oasis of Bou-Saada, much to Cleaver’s disapproval. Having recently returned from a conference in North Korea, Cleaver had become a devotee of Kim Il Sung. He now believed that the Panther strategy of uniting with white radicals of the psychedelic counterculture had been mistaken.[ix] And it was not just white hippies that Cleaver wanted to disassociate his movement from. In Leary’s words, ‘Eldridge invented himself a security crisis. Like Nixon, like Brezhnev’:

‘Everything the Panthers did was in the name of security. We were constantly lectured on the precariousness of our situation; American police were after us. All Algerians were racists. The town was crawling with enemies. Our foes were multiplying. The other national liberation fronts turned out to racist too and riddled with double agents. Even our American allies became deadly rivals one-by-one: Angela Davis, Huey Newton, Stokeley Carmichael – all running-dog lackeys of imperialism’.[x]

The CIA’s top-secret Algeria operation had been set up after Cleaver’s arrival in Algiers in 1969. The CIA, as later revealed by Seymour Hersh in the New York Times had recruited Black Americans to spy on members of the Black Panther Party both in the United States and in Africa, especially Algeria. One agent gained access to the personal living quarters of Cleaver in Algeria in the late 1960’s. Another later boasted to his colleagues that he had managed to penetrate Cleaver’s Algerian headquarters ‘and sat at the table’ with him. The CIA’s aim, in the case of the Black Panthers living abroad, was to ‘neutralize’ them; ‘to try and get them in trouble with local authorities wherever they could’.[xi]

According to Leary, the problem with Cleaver was that he was ‘totally American. He doesn’t want to change the system, he just wants to run it’.[xii] On one occasion Cleaver pulled a gun on Leary and threatened to denounce him to the Algerian authorities for his activities with LSD if a sum of $10,000 was not forthcoming. On 9 January 1971, Cleaver ‘imprisoned’ the Learys, placing them under armed guard. A CIA document dated 12 February 1971 noted:

‘Panther activities have recently taken some interesting turns. Eldridge Cleaver and his Algiers contingent have apparently become disenchanted with the antics of Tim Leary… Electing to call their actions protective custody, Cleaver and company, on their own authority, have put Tim and Rosemary under house arrest due most probably to Leary’s continued use of hallucinogenic drugs’.[xiii]

Tim and Rosemary were fearful about ever getting out of Cleaver’s personal prison. They had good reason to be. Unknown to Leary, months earlier Cleaver had shot dead his fellow exile, Clinton Smith, after accusing him of amorous intentions towards his wife, Kathleen Cleaver. Byron Booth, who witnessed the murder, helped Cleaver bury Smith’s body in the mountains and fled Algeria the next day.[xiv]

Cleaver’s imprisonment of the Learys came just as a serious split was developing between Cleaver’s faction and the California-base leadership. Panther leaders Huey Newton and David Hilliard wanted the party to focus on community service and avoid any armed actions beyond self-defense; others, such as Cleaver, wanted to continue and extend offensive armed struggle. Some activists had given up on the Black Panther Party and joined the Black Liberation Army. The Panther split became public in mid-February 1971. In the weeks and months that followed, four members of the party in both factions were killed in tit-for-tat shootings.

As reports reached the Panthers in the US about the disappearances of Clinton Smith and Byron Booth, suspicions of murder began to spread, and Cleaver began to fear being overthrown by a coup at his own headquarters. The Learys took advantage of Cleaver’s distraction and escaped his clutches. Leary made contact with officials of the Algerian government, who told him that they themselves were unhappy about Cleaver’s activities in their country and assured the Learys that they could stay for as long as they wished. Now under the protection of the Algerian government, Leary was visited by the English writer and dope-dealer, Brian Barritt, whose rebel status was very different from Cleaver’s. Barritt, who had been introduced to LSD by Alex Trocchi in London in the mid-1960s, was an enthusiastic student of ‘English Magick’ in the ‘tradition’ of John Dee and Alistair Crowley. He was to become Leary’s co-author on the forthcoming book, Confessions of a Hope Fiend, in Switzerland, the next stop on the Leary’s journey. Leary’s archivist, Michael Horowitz, summarises Confession of a Hope Fiend as the story of his prison escape flight to exile and ‘revolutionary bust’ by the Black Panther Party leader ‘after he either won or lost the debate on the role of psychedelic drugs in the revolution’:

‘In Algeria, the role of Hassan-i-Sabbah – the founder of the hashishin and the first recorded person to brainwash with euphoric drugs – was not necessarily up for grabs. The Aleister Crowley persona emerged during an acid trip in the Sahara. But survival dictated another space time co-ordinate’[xv].

Hotel Abyss

In April 1971, Leary accepted an invitation to give a talk at Aarhus university in Copenhagen. The Learys flew first to Geneva and sought advice from his friend, Pierre Benoussan. He advised them to stay in Switzerland because he thought that if they went to Denmark, they were certain to be arrested and deported to the US. Benoussan gave them the address of Michel Hauchard, arms dealer for the Palestinians, convicted fraudster and jailbird.[xvi] Hauchard, as gentleman rogue, felt obliged to help Leary as a persecuted philosopher. He provided the Learys with a chalet at a Lake Geneva ski resort. Thanks to Hauchard’s generosity, Rosemary Leary was now able to seek the fertility treatment she needed to become pregnant. Hauchard’s largesse had a price. Leary had to promise he would not leave Switzerland and had to sign away in advance half the royalties on the book, Confessions of a Hope Fiend.[xvii] But for the moment Leary had landed in the lap of luxury, and revolutionary politics was now irrelevant to him. As Higgs puts it,

‘Indeed, just three months after pledging “eternal solidarity” to the Brazilian Marxists who had escaped from jail and fled to Algiers, he found himself drinking with the Brazilian aristocrats who had jailed them in the first place. “Torture,” one of them told him, “was nothing more than an advanced form of acrobatics.” By now Tim was quite used to imprinting an entirely new worldview whenever he found himself in a different environment, but rarely was the process as effortless as this’.[xviii]

Hauchard provided the Learys with a lawyer to obtain temporary Swiss residence for them. When, in June 1971, Tim was arrested by the Swiss police to face an extradition request from the US government, the lawyer got him out of prison on health grounds. In December, Leary’s appeal against extradition was upheld by the court, on condition that he would keep out of subversive politics and stay away from illegal drugs; the first was easy, the second was out of the question for Leary, although he believed he could take his daily doses of acid discreetly. The downside was that the court ruled he would have to leave Switzerland before the end of the following year, 1972.

In September 1971, Leary got to meet Albert Hoffman, the discoverer of LSD. Hoffman told Leary that it was regrettable that investigations into LSD and psilocybin had ‘degenerated’ so much that continuance of psychedelic research in the academic milieu had become impossible:

‘In this conversation I further objected to the great publicity that Leary sought for his LSD and psilocybin investigations, since he had invited reporters from daily newspapers and magazines to his experiments and had mobilized radio and television. Emphasis was placed on publicity rather than objective information. Leary defended his publicity program because he felt it had been his fateful historic role to make LSD known worldwide. The overwhelming positive effects of such dissemination, above all among America’s younger generation, would make any trifling injuries or regrettable accidents as a result of improper use of LSD unimportant in comparison, a small price to pay’.[xix]

David Solomon travelled from England to Switzerland to see Leary and secure a role as an agent negotiating with publishers.[xx] Another arrival in the Learys’ Swiss household was Dennis Martino, Leary’s hash-smuggling son-in-law from a previous marriage. He was wanted in the US for jumping parole, but in December 1972 made a trip to the US. This should have raised Leary’s suspicions, but didn’t. Leary and Brian Barritt ventured into music production with German krautrockers. Barritt got Leary into heroin, until after few weeks Leary wisely decided to quit. During this period Leary was constantly on LSD, though could function rationally in his day-to-day interactions. Leary had now decided that ‘whereas the space games are survival, power and control, the corresponding time games are sex, dope and magic’.[xxi]

By this time Rosemary Woodruff Leary had had enough of Tim’s new life and entourage. Rosemary took up with John Schewel, an associate of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, and spent the next twenty years hiding out in various parts of the world.

Leary hooked up with an aristocratic Englishwoman, Joanna Harcourt Smith, who was introduced to him by Hauchard. Meanwhile the US authorities were renewing pressure on the Swiss by drumming up more charges against Leary, accusing him of being ‘the godfather of the largest drug-smuggling ring in the world’ – the Brotherhood of Eternal Love (the charges were later dropped for lack of evidence).[xxii] At the end of 1972 Leary and Joanna moved to Vienna. Joanna wanted to take Leary to Ceylon, where she had rich relatives to put them up. Then, fatefully, Dennis Martino arrived in Vienna. He suggested that rather than head straight for Ceylon, the three of them should go firstly to Afghanistan, where, he assured them, he had Brotherhood of Eternal Love contacts who would help them. Leary, accompanied by Joanna Harcourt-Smith and Dennis Martino arrived in Afghanistan in January 1973. In Kabul, former CIA agent Terrence Burke was now working in Kabul for the US Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs and was monitoring the brothers Aman and Nasrullah Tokhi, who were supplying the Brotherhood of Eternal Love with large shipments of hash. The Afghan authorities provided Burke with copies of American travellers’ embarkation and disembarkation cards, so he was thus warned of the impending arrival of the Learys and Martino. Burke arranged for US Embassy staff disguised as Afghan immigration officers to be on hand to confiscate Leary’s fake passport. Burke then persuaded the Afghan authorities to deport Leary. Dennis Martino, also a fugitive, struck a deal with Burke in Kabul to become an informer. Or was he one already? What is certain is that Martino, spirited back to California after Leary’s deportation from Afghanistan, arranged for at least two dozen of his dope-dealing associates of the Brotherhood to be arrested.[xxiii]

Eldridge Cleaver left Algeria for France in 1972 and went into hiding. He returned to the USA in 1977 a born-again Christian. After some plea-bargaining and public repentance for his political past he got away with a sentence of 1,200 hours community service for the outstanding assault charge.[xxiv] His Black Panther rival, Huey Newton, came out of prison in 1970. He failed to revive the party and fell into gangsterism and cocaine addiction.

Leary ‘Co-operates’

At his trial in March 1973 for the 1970 prison escape, Leary was sentenced to five years imprisonment in addition to the twenty he had been serving. For management of his affairs outside of prison Leary still relied on Joanna Harcourt-Smith. In November, 1973, Leary was transferred from Folsom to Vacaville Prison. There he learned that Martino had become a government snitch and that Joanna was sleeping with him. When Allen Ginsberg met Joanna Harcourt-Smith during a prison visit, he told her he suspected she might be a ‘double agent’. In response, Joanna turned to Leary and said ‘Oh, he just hates women’. Leary simply threw up his hands in exasperation. But for Leary himself, in this latest reality tunnel informing was taking on a new meaning: Leary, in return for early release, was prepared to talk to the FBI.

On the evidence of Leary’s autobiography, the ‘Leary Turns Fink’ story, which gained wide circulation in the late seventies, was, in part at least, the product of an FBI counter-offensive aimed at blunting the revelations about the Bureau’s own illegal actions against dissidents. When a transcript of Leary’s testimony was leaked to journalist, Jack Anderson, Leary complained that it made it sound as if he was testifying against anyone who had ever offered him a joint. But the story severely damaged Leary’s reputation among his followers. Becoming a political extremist under extreme circumstances might have been understandable; but becoming a renegade fink put him beyond the pale. After the FBI milked Leary for all the information they thought they get, Leary was finally given his freedom in April 1976.

According to Leary, he only wanted to convince the FBI that people like the Weather Underground and Brotherhood of Eternal Love were really just all-American kids who had grown a little too enthusiastic about realising their ideals. Regarding his ‘motives’ for talking, Leary said that he wanted an ‘intelligent, an honourable relationship’ with Government institutions:

‘So this does not just turn someone over to get out of prison, it’s part of a longer range plan of mine… I intend to be fully active in this country in the next few years however the things turn out… I’m never going to work at it illegally ever again, but I would prefer to work constructively and collaboratively with intelligence and law enforcement people that are ready to forget the past…’[xxv]

Leary did talk to the FBI about the Weather Underground and name names, but in the long run the group was not impacted by Leary’s testimony. By the mid-1970s the Weather Underground leadership had grasped the reality that they weren’t going to be able to bomb US Imperialism out of existence. Bill Ayers and Bernadine Dohrn believed they could avoid federal prosecution and lengthy prison sentences because of illegal wire taps and reluctance on the government’s part to reveal sources and illegal methods. Ayers and Dohrn favored a strategy of ‘surfacing’ as above ground revolutionaries. Bernadine Dohrn’s sister, Jennifer, organised an umbrella organization of radical groups which was named the Prairie Fire Committee (inspired by Mao Zedong’s polemic against ‘pessimism’: ‘A Single Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire‘).

In 1977 a pamphlet appeared entitled The Split of the Weather Underground Organization – Struggling Against White and Male Supremacy. This contained an abject ‘confession’ by Bernadine Dohrn, admitting to charges of racial and sexual chauvinism, and ‘opportunism’. An article by Clayton Van Lydegraf, ‘In Defense of Prairie Fire’, indicated that the new ‘line’ was a very orthodox Marxist-Leninism committed to supporting armed actions. But Van Lydegraf’s takeover of what was left of the Weather Underground’s military structure proved disastrous. Since 1969 the FBI had largely failed to penetrate the group, but they soon succeeded in doing so when the Bureau’s Weather hunters infiltrated a couple of undercover agents into the West Coast Weather Underground Organization as firearms instructors; one of whom actually moved in with Van Lydegraf as his housemate. In 1977, Van Lydegraf, and several Weather Underground members were arrested for plotting to bomb the offices of a California state senator and got two-year prison sentences. This essentially finished the Weather Underground. All three of the groups Leary had operated with during his fugitive period – the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground – were broken up largely within that timespan. In between 1970 when he escaped prison and 1976, when he was released, Leary created for himself one ‘reality tunnel’ after another: first with the Weather Underground, then with Cleaver’s Black Panthers, then with Hauchard, then finally with the FBI. As John Higgs puts it:

‘Enlightenment thinkers assumed that everyone operates in the same reality, but that, Leary believed, was not true on a practical level. Concepts, relationships and events were now relative, and could only be really understood when analysed alongside the reality tunnels that created them’.[xxvi]

As Leary said of his first LSD trip with Michael Hollingshead ten years earlier,

‘From that day I have never lost the sense that I am an actor, surrounded by characters, props and sets for the comic drama being written in my brain’.[xxvii]

[i] Quoted in Bryan Burrough, Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age.

[ii] John Higgs, I Have America Surrounded: The Life of Timothy Leary, p.125.

[iii] Quoted in Lee and Shlain, Acid Dreams, p.230.

[iv] Paul Krasner, ‘A Game of Mind Tennis with Timothy Leary’, in Forte (ed.), Timothy Leary p.122.

[v] Leary, Flashbacks, ps 301-2.

[vi] Higgs, p.127.

[vii] Forte, Timothy Leary, p.85.

[viii] Elaine Mokhtefi, Algiers, Third World Capital: Freedom Fighters, Revolutionaries, Black Panthers , Chapter 5.

[ix] Donn Pearce, ‘Leary in Limbo’, Playboy, July 1971.

[x] Leary, Flashbacks, p.304.

[xi] Seymour Hersh, ‘Huge CIA Operation Reported in US Against Anti-War Forces’, New York Times, 22 December, 1974; ‘CIA Reportedly Recruited Blacks For Surveillance of Panther Party’, New York Times, 17 March 1978.

[xii] Timothy Leary, Confessions of a Hope Fiend, p240. Quoted in John Higgs, I Have America Surrounded, p.138.

[xiii] Lee and Shlian, ps.268-9.

[xiv] Mokhtefi, op.sit.

[xv] Higgs, ps.139-140.

[xvi] Lee and Pratt, ps.340-2.

[xvii] Leary, Flashbacks, ps.300-310.

[xviii] Higgs, p.158.

[xix] Albert Hoffman, ‘My Meetings With Timothy Leary’, in Forte, op.cit. ps.89-90.

[xx] Tendler and May, p.112; Lee and Pratt, ps.340-342.

[xxi] ‘Prophet on the Lam: Timothy Leary in Exile’, in Forte op.cit. p.98.

[xxii] Forte, p.70.

[xxiii] Higgs, p.223.

[xxiv] Mokhtefi, op. cit.

[xxv] Timothy Leary, The Politics of Psychopharmacology (Ronin Publishing: 2009), p.110.

[xxvi] John Higgs, I Have America Surrounded: The Life of Timothy Leary, ps.46-48.

[xxvii] Leary, Flashbacks, p.119.

(27 November 2020)

(27 November 2020)