Review by David Black

#sponsored Amazon Link

Lyndal Roper’s book, Summer of Fire and Blood: The German Peasants’ War (Basic Books, 2025) is the product of decades of scholarly research, including treks all over Germany to trace the events and places she writes about. Her approach is ‘to understand the world the peasants inhabited through uncovering the rich details of their daily lives, and to reconstruct their beliefs…’

Peasant Life

In 16th century Germany the woodlands provided timber for house-building; animals and birds for hunting; and acorns, nuts and berries to feed pigs. Meadowlands fed sheep and cattle. Strip-farming yielded new crops. Rivers, streams and lakes teemed with fish to eat, and powered machinery such as flour mills.

Despite these rich natural resources, the world of the German peasants was unfree, impoverished and unjust. In the Holy Roman Empire headed by Charles V, Archduke of Austria, the myriad princedoms of Germany were a decentralising factor: with lords left free to impose on their peasants a heavy burden of ground rents, tithes, taxes, and tolls; as were the monasteries, which stored vast quantities of flax, grain, fruit, oil and cheese. The monasteries were themselves producers of commodities, especially beer and wine, but unlike their secular competitors, paid no tax on them.

The peasants had to perform onerous labour services for the lords and prelates, such as sowing and harvesting, making carts, and even such idiocies as collecting snail shells for courtly women to wind their sewing threads. Peasants were not allowed to hunt, but had to keep and feed the lords’ hunting dogs, and put up with hunts riding over their land and destroying their crops.

Many peasants, especially in the south-west were serfs bound to their lords’ land in such a way that the lords owned the serfs’ bodies and reproductive abilities:

‘…the wide-ranging rules of what counted as incest devised by the church meant it was virtually impossible to find someone owned by the same lord who was not related and of marriageable age.’

Even ‘free’ peasants could be fined for marrying outside of the manor.

Reformation and Revolution

It is impossible, Roper writes, to grasp the possibilities and limits of the Reformation without understanding the Peasant War as ‘the giant trauma at its centre’, and vice-versa.

In 1517 Martin Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg. The Theses attacked the abuse and corruption of the church’s practises – worship of fake relics, Virgin Mary idolatry, sale of indulgences, ‘tickets’ for pilgrimages to sites of alleged miracles, restriction of communion wine to the clergy, etc. His missive implied what many had long thought: that the monasteries, which sucked the wealth of the communities without giving anything back, had no legitimacy and no reason to exist. Furthermore, Luther’s call for Reformation was, at the same time, literally a call to arms, quoting the words of Jesus that he had come not to bring peace, but a sword.

Luther’s theses were immediately translated from Latin to German, printed and distributed in the streets of Nuremberg. His pamphlet of 1520, The Freedom of a Christian, circulated in German, and was aimed, he wrote, at ‘the unlearned – for only them do I serve’.

The new invention of moveable type for printing brought about the first ‘communications revolution’. No longer would reading, writing and education be monopolized by the scribes of the church. The printed word had the potential to make knowledge available to all.

In February 1525 Albrecht, who led the warrior monks of the Teutonic Knights, declared for the Reformation and became a duke, effectively founding Prussia. As Luther was Albrecht’s leading theologian, this event was a triumph for the Reformation. However, the issue for many was how to interpret the concept of justice in the ‘true’ Christian gospel. Luther, in The Freedom of a Christian, stated that on the one hand the Christian believer is a free lord of all things, and on the other hand, a dutiful servant of everyone. Luther later insisted that he meant ‘freedom’ only in the religious sense, and ‘duty’ in the sense of submission to feudal power, no matter how unjust. However, for radical interpreters of the Reformation, being ‘the free lord of all things’ meant the freedom to enjoy the God-given fruits of the earth. In Roper’s interpretation of peasant demands, in the broad sense:

‘Woods must be free, water must free. the animals in the forest and the birds must be free for people to hunt. Here, “free” meant not sovereign, but free for people to use. These demands were not new, but they formed part of a religious vision’.

The Twelve Principles of the peasants’ Christian Union were formulated by Sebastian Lotzer, a former Lutheran theologian who joined the peasants’ bands and became one of their leaders. The Principles called for the freedom of congregations to elect their preacher, the abolition of serfdom, restoration of common land that had been seized by the nobles, and an end to arbitrary justice which rigged in favour of the rich and powerful.

Movement

In the winter of 1524-5, the tythes had been paid to the lords and prelates, the granaries filled, and the animals butchered or brought into the shelter of the barns on the ground floors of houses. Women turned to spinning; men to woodwork.

Since Hans Böhm. the visionary ‘Drummer of Niklashausen’, was executed in 1476 for leading a peasant rebellion, there had been regular outbreaks of dissent. What was different this time was that the peasant mobilisations of the previous year -1524 – had assumed organisational form, of the Bands of Brothers, who took oaths of loyalty to the Words of the Gospel. So, as winter was no time take on the lords, the peasants used the slower pace of life to ‘think, gossip, organise and prepare’.

The preparations for rebellion took the form of a ritual: a peasant band would gather together and swear an oath of loyalty to the Brotherhood; then send an invitation to the next village, announcing ‘We have formed a band of brothers to support the gospel and we invite you to come to us’ and, with a hint of menace, adding ‘and if you will not come to us we will come to you’. The recipient would then summon the community, the Gemeinde, which, as the congregation of church goers, was also the collective of farmers and craftsfolk who managed use of land and protection of livestock.

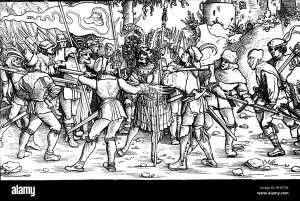

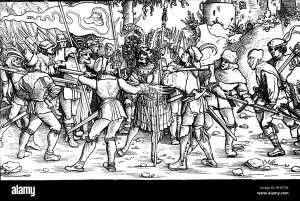

In early spring the rebellion got underway. Within weeks it spread from the Swiss border in the south, through the Black Forest to Swabia; up the Rhine to Alsace in the west, and through the valleys into Franconia. The peasant bands moved through valleys and forests, looting and destroying hundreds of monasteries, abbeys and castles. They proceeded – unlike the armies of the nobles – largely without stealing from the locals, killing or raping. Lords, monks and nuns were subjected to the humiliations of being sent packing; some were invited to join the rebels, and some did, though many of them claimed later they had been coerced into doing so.

Typically, the occupation of monastery would begin with a Saturnalian revel as the peasants helped themselves to vast stores of food and communion wine, and destroyed saintly statues and painted images. The libraries were sacked; largely because the peasants associated written records with tythes and taxes. The raids on monasteries and castles provided the army with hordes of money, precious objects to be sold, and armaments. Also, as Roper describes the peasants’ actions,

‘This was not mindless vandalism; they intended to destroy the relics of the old religion and its reverence for holy objects, which felt like a giant fraud in light of the truth that Christ himself had bought their freedom.’

Lords and abbots sent out appeals for military assistance but, as the armies of the Swabian League were busy fighting the French in Lombardy, little help was forthcoming. The peasants conquered by sheer force of numbers. Likewise in those towns and cities patrician overlords were overthrown in a ‘wave of anticlericalism and antimonasticism’ which took in support for the peasants – as they were all oppressed by the same class of tyrants.

Holy War

At the height of the War a pamphlet probably written by Sebastian Lotzer. entitled To the Assembly of the German Peasantry, discussed the tyranny of Ancient Rome and warned, ‘Listen, dear brothers, you have embittered the hearts of your lords so greatly with an excess of gall that they will never be sweetened again’. The current rebellion was so far advanced any turning back would end in mass slaughter and a new stage of ‘slavery’.

Roper doesn’t doubt that the peasants could not match the military training, fire-power and armoured cavalry of their enemies, but observes that they were not incompetent. They had arms, including guns, liberated from captured castles.

The ranks of the Peasant army included former mercenaries, who knew tactics. One such was Hans Müller, who led a band known as the Black Foresters. Müller captured Freiburg on 12 May and led a march to Hegau where the army were besieging the Swabian League’s stronghold at Zell. In mid-June, Müller’s fighters were overwhelmed by superior numbers, after which he was captured and executed.

Preacher Jakob Wehe was one of the leaders of a 4,000-strong peasant army which took on the cavalry of the Swabian League at Leipheim. Wehe assured the peasants that ‘by a special providence of God’ they would triumph against a much better armed enemy. He was wrong; the peasants were scattered and slaughtered. 700 were imprisoned in Laupheim, including Wehe, who was executed.

Florian Geyer, a lord who joined the peasants, formed a troop of cavalry which fought many successful battles until June, when Geyer was killed in battle by the forces of the Elector Palatine.

Thomas Müntzer assembled an enormous peasant army on the mountain of Frankenhausen, Thuringia on 15 May 1525 to take on the joint forces of the Lutheran Philip I of Hesse and the Catholic Duke George of Saxony. The defences of the peasant force of 8000 were the high ground, which they held, and the circle of their wagons. The first salvos of enemy artillery panicked and scattered the defenders, who were then cut down in their thousands by charging cavalry. Müntzer was captured, tortured into ‘repentance’ (could repentance ever be extracted under torture?) and executed.

One factor in the Peasant War’s outcome was the failure of the peasants’ evangelisers to persuade the miners to rise, even though many of them had left the mines to join the peasant bands. Roper suggests that a ‘theology of the natural world’, which she assigns to the peasants, may have had ‘less appeal’ the miners. The mining industry was expanding within the first globalisation of capitalism in its mercantile stage. In rural Germany forests were being felled to supply charcoal for smelting; streams supplied the water to clean mined ore and got back fish-killing pollutants. The mines were making a lot of money for the owners, who felt confident enough to grant concessions.

Aftermath

The peasants were defeated before they could ‘put plans for a new future into action’. A hundred thousand peasants were slaughtered during or after the War. Towns which had sided with peasants were retaken and suffered collective punishment. Luther, in his infamous pamphlet, Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants, cheered on the brutality of the nobility.

Due to the peasants’ massive destruction of monasteries and the castles, the power of the abbots and lower nobility never recovered. The lot of the mass of peasants did not improve and many had to endure a ‘Second Serfdom’. The decentralising power of the princes was consolidated further, ensuring that the unification of Germany didn’t happen for another 350 years.

In the aftermath of the Peasant War the halo of the Reformation lay blooded in the dust. Luther’s outlook, writes Roper, shaped ‘insistence on obedience to secular powers, no matter how unjust.’ This legacy, she suggests, may have shaped the Lutheran church’s accords with both National Socialism and the East German regime.

The Anabaptists endorsed Müntzer’s biblical vision of Omnia sunt communia but at the same adopted a pacifist stance. Their principle of adult baptism as affirmation of faith against infant baptism was anathema to Lutheran and Catholic practices. Renouncing violence did not protect the Anabaptists from being imprisoned, burnt at the stake or forced into exile. The preacher Balthasar Hubmaier found common cause with the Anabaptists, but as a Müntzer follower he couldn’t accept pacifism. Hubmaier was burnt at the stake in Moravia by the Austrians.

Marxism and the Peasants

Roper is highly critical of Friedrich Engels’ The Peasant War in Germany and Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, both of which were published in the wake of the 1848-49 Revolutions. Both, she contends, ‘relegate peasants to the sidelines of history’.

Engels, looking back 300 years, found the same forces – revolutionary and counter-revolutionary – which had emerged during the 1848 Revolutions. Luther was a proto-bourgeois liberal: riding to power on a wave of popular protest, then making peace with the forces the people were protesting against. Thomas Müntzer’s ‘All Belongs to All’ movement was the communist forerunner of the ‘proletarian party.’ But this role for Müntzer is a difficult fit. Certainly Müntzer’s apocalyptic prophecies lacked any practical vision of a free society. And (as Engels admits) Müntzer was no military leader. He led his forces to the disaster at Frankenhausen because he had discerned a prophecy of victory in a dream he had.

Roper sees Engels’ Müntzer as ‘trapped like an impotent time-traveller able to articulate “the ideas of which he himself had only a faint notion” but incapable of “transforming society”.’

The difficulty in describing the Peasant War as a putative ‘bourgeois’ revolution with an ‘undeveloped’ proletarian offspring is in explaining the absence among the actual revolutionaries – the peasants – of concepts such as ‘progress’ and ‘democracy’ – and other ideological pillars of bourgeois society. ‘Freedom’ meant something quite different from ‘Liberty’ as espoused by later opponents of feudalism in the name of the ‘individual’. ‘Freedom’ for the German peasants, meant Christian Brotherhood, which implied collective social responsibility – though it meant also upholding patriarchy and side-lining the role of women. Roper speculates that the masculinism which bonded the Brotherhood may have heightened their illusions of martial invincibility.

Turning to Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Roper notes that he compares the mass of small-holding peasants in post-1848 France with a ‘bag of potatoes’. Here, Marx was comparing the small-holding, debt-ridden peasantry of 1850 unfavourably with the ‘flower of the peasant youth’ that had fought in the Revolutionary armies in 1790s.

In Germany in 1850, the peasants were oppressed and impoverished by the nobility (junkers). But Lassalle, the leading German socialist of the time, regarded the peasants, in 1850 as in 1525, as ‘reactionary’. In the 1875 Critique of the Gotha Program Marx objected to the Lassallean’s lumping together of peasants, artisans, petit-bourgeoisie and feudal lords as ‘only one reactionary mass’ in relation to the working class; a position which effectively excluded the peasantry from playing any revolutionary role, and abandoned them the rule of the junkers. The Lassalleans’ demand for ‘state aid’ ‘under the democratic control of the working people’ ignored that ‘in the first place, the majority of the “working people” in Germany consists of peasants, not proletarians’.

Marx agreed with Engels on the necessity of a merciless struggle against the feudal masters, writing on 16 August 1856,

‘Everything in Germany will depend upon whether it will be possible to support the proletarian revolution by something like a second edition of the Peasant War. Only then will everything proceed well.’

Roper recognises the ‘radical edge’ of Peasants’ War as ‘the sheer breadth of their ideas, which addressed the environment, human agency and animals’. She adds:

‘These not issues that interested Marx and Engels because they did not point the way forward to the industrialisation of the future. But they are questions that confront us now. Who owns the natural resources, timber, rivers, ponds and common land? Who controls energy sources? How can we till the land sustainably? In a way that is fair to both small and big producers? How can wealth be shared equally?’

Roper’s point is that these questions were posed by the peasants of 1525. And are all still valid. But was Marx himself really a productivist, looking forward ‘to the industrialisation of the future’? Kohei Saito contends in Marx in the Anthropocene that the later Marx was beginning to grasp a non-productivist vision of ‘de-growth’ communism, and even abandoning historical materialism as a program of industrialisation. Saito sees Marx as addressing how the transhistorical, interactive relation of humans with the rest of nature undergoes a ‘metabolic rift’ which is historically specific to capitalism. Marx was studying, Saito writes, ‘…various practices of robbery closely tied to climate change, the exhaustion of natural resources (soil nutrients, fossil fuel and woods) as well as the extinction of species due to the capitalist system of industrial production’.*

As a feminist and environmentalist Roper sees that the modern world can learn from the 16th century peasants: the sense of ‘community’ – with each other and with ‘the fruits of air, land and sea’ – in free ‘spiritual’ expression, but free of intolerance and exclusion by gender, religion or creed. The question of the ownership and control of natural resources, energy, land and wealth confronts us now as then.

*David Black, ‘How Green was Karl Marx: Kohei Saito and the Anthropocene’, 23 June 2023 https://imhojournal.org/articles/how-green-was-karl-marx-on-kohei-saito-and-the-anthropocene

This article first appeared in IMHO Journal

Lost Texts Around King Mob, by Dave and Stuart Wise. with contributions from John Barker, Chris Gray, Ronald Hunt, Phil Meyler and Fred Vermorel

Lost Texts Around King Mob, by Dave and Stuart Wise. with contributions from John Barker, Chris Gray, Ronald Hunt, Phil Meyler and Fred Vermorel Dialectical Butterflies: Ecocide, Extinction Rebellion, Green and Rewilding the Commons – an Illustrated Derive, by Dave and Stuart Wise.

Dialectical Butterflies: Ecocide, Extinction Rebellion, Green and Rewilding the Commons – an Illustrated Derive, by Dave and Stuart Wise. King Mob: the Negation and Transcendence of Art, by Dave and Stuart Wise

King Mob: the Negation and Transcendence of Art, by Dave and Stuart Wise A Newcastle Dunciad: Memories of Music and Recuperation, by Dave and Stuart Wise

A Newcastle Dunciad: Memories of Music and Recuperation, by Dave and Stuart Wise Building For Babylon: Construction, Collectives and Craic, by Dave and Stuart Wise

Building For Babylon: Construction, Collectives and Craic, by Dave and Stuart Wise Red Chartist: Complete Annotated Writings, and her Translation of the Communist Manifesto, by Helen Macfarlane

Red Chartist: Complete Annotated Writings, and her Translation of the Communist Manifesto, by Helen Macfarlane Red Republican: Complete Annotated Works of Helen Macfarlane and Translation of the Communist Manifesto

Red Republican: Complete Annotated Works of Helen Macfarlane and Translation of the Communist Manifesto  Red Antigone: The Life and World of Helen Macfarlane 1818-60, by David Black

Red Antigone: The Life and World of Helen Macfarlane 1818-60, by David Black Psychedelic Tricksters: A True Secret History of LSD, by David Black

Psychedelic Tricksters: A True Secret History of LSD, by David Black LSD Underground: Operation Julie, the Microdot Gang and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, by David Black

LSD Underground: Operation Julie, the Microdot Gang and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, by David Black