20 March 2024 –

BPC Publications (London) announces release of two titles this week in the WisEbooks Series, compiled by, and featuring, Dave Wise and Stuart Wise, founders of King Mob.

Dialectical Butterflies

Ecocide, Extinction Rebellion, Greenwash and Rewilding the Commons – an Illustrated Dérive

Dave and Stuart Wise

This is published as an ebook because its 80 colour photographs would be too costly to print.

Beautifully illustrated, Dialectical Butterflies is a psychogeographical exercise in butterfly preservation as part of the environmentalist, anti-capitalist struggle against ecocide, The lifelong fascination of David Wise and his late twin, Stuart, with the ecology of butterflies goes back to their involvement in the mid-1960s surrealist-inspired radical arts scene in Newcastle. From their contact with the Situationist International the Wise brothers adopted the concept of ‘recuperation’ which they see exemplified in today’s ‘greenwashing’ PR exercises. Their latter-day rewilding campaign is effectively a post-situationist Longue Dérive through the relatively forsaken terrains of derelict industrial sites and zones of autonomy in northern England; as well as the contested public space of Wormwood Scrubs in London.

_________________________________________

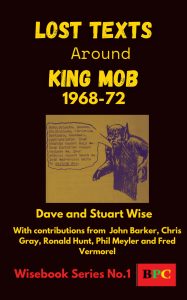

Lost Texts Around King Mob 1968-72, published as an ebook in January 2024, is now by popular demand available as a paperback.

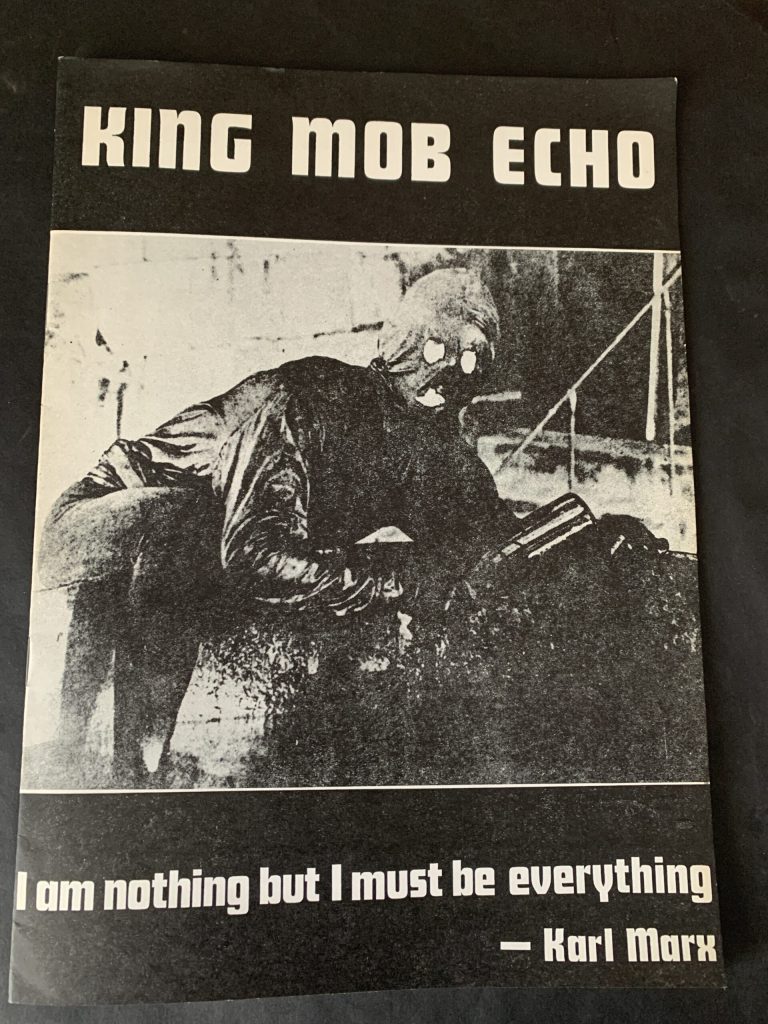

King Mob was initially a coming together in London of members of the English section of the Situationist InternationaI and like-minded individuals from Newcastle associated with the anti-art magazine, Icteric, and the Black Hand Gang.

Following Guy Debord’s expulsion of the English members of the SI in December 1967, the King Mob Echo was co-founded in April 1968 by former SI member, Chris Gray and ‘friends from the north’, Dave and Stuart Wise.

The material in this collection by King Mob writers and their associates still has a power to provocatively invigorate and open up new directions of thought and action emanating from a subversive critique of culture. For the most part, these documents have been forgotten and therefore never archived in the libraries of art history and the ‘popsicle academy’ of media/music studies. Indeed, they had to be rescued from what Marx called “the gnawing criticism of the mice”.

Contents

- Dave Wise and Stuart Wise (King Mob), Introduction: By way of an explanation…

- Ronald Hunt (Newcastle-based art historian), The Arts in Our Time: A Working Definition; The Great Communications Breakdown, (1968)

- Dave Wise and Stuart Wise, Culture and Revolution (1968)

- John Barker (Angry Brigade) Art+Politics = Revolution (1968)

- Fred Vermorel, (music writer who collaborated with Malcolm McClaren in formulating Punk Rock), The Rewards of Punishment and On Whom Can the Workers Count? (1970)

- Chris Gray (Situationist) and Dave Wise, Balls! (1970)

- Phil Meyler (Dublin associate of King Mob), The Gurriers (1968) and Notes from the Survivors of the Late King Red (1972)

The book is dedicated to Stuart Wise, 1943-2021

_________________________________________

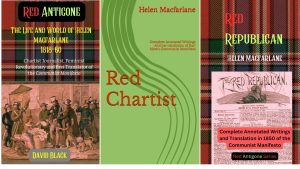

Red Antigone: The Life and World of Helen Macfarlane 1818-60 – Chartist Journalist, Feminist Revolutionary and Translator of the Communist Manifesto

By David Black

By David Black

Paperback (110 pages) – March 2024

From Everyone has a favourite Chartist by Stephen Roberts, Chartism and the Chartists 2016

The Marxist historian David Black certainly has a favourite Chartist who he can’t shake off. That Chartist is Helen Macfarlane, who contributed to the Chartist press for just one year, 1850. Black has just released a collection of Helen Macfarlane’s journalism (Helen Macfarlane: Red Republican, 2014). This isn’t his first book about this undeniably interesting figure. And it won’t be his last. A full-length biography is under way. What we have for now, though, is an anthology of Macfarlane’s writings for Julian Harney’s journals, the Democratic Review (April-September 1850) and the Red Republican (June-November 1850). Reprints of these journals appeared in the 1960s, but aren’t that easy to find these days. So Black has done those who want to read Macfarlane’s contributions a favour. And they are so much easier to read than the original columns (Black thanks Keith Fisher who undertook the laborious task of typing them out). Be in no doubt, Black is a fan … ‘her words jumped off the page at me’, he writes, ‘no one had ever before written like this in the English language’

So who was Helen Macfarlane? She was undeniably a remarkable woman. Born into a well-to-do Glasgow family of calico-printers, she became a governess after the family business was ruined in 1842. She appears to have been radicalized whilst living in Vienna in 1848 &, back to London, came into the orbit of Marx. She translated the Communist Manifesto & sent her own political writings to Harney for publication. Black is certainly right about the quality of her work. What Macfarlane wrote is a cut above a lot of the material that appeared in late Chartist journals. Read ‘Fine Words (Household or Otherwise) Butter No Parsnips’ (reptd. here pp. 53-8) and you’ll see what I mean…

This is a fascinating story & certainly whets the appetite for the full-length biography Black promises.

AND HERE IT IS

Red Antigone is also available as an Ebook – March 2024

The first title issued in the Red Antigone Series, this is the first biography of Helen Macfarlane, Scottish-born feminist philosopher and shooting star of late-Chartist journalism.

Born into a family of gentrified Highland lairds who moved to Glasgow and became rich capitalists, Helen Macfarlane was a child of the Scottish Enlightenment. Educated by the males in her family, she went further than any of them in her radicalism. Key sections of the Communist Manifesto, which she translated, explained for her how capitalist development led to disruption, such as the bankruptcy of the Macfarlane calico business, and unemployment and poverty for masses of workers. Red Antigone is also the saga of her ‘clan’ – of found and lost riches, and risky adventure, and tragedy – and its, at times, conflictual relationship with her revolutionary politics. Alone amongst British radicals, her interpretation of ‘continental socialism’ was based as much on her understanding of Hegel as on her involvement in the 1848 Revolutions. Marx praised her as an ‘original’ and a ‘rara avis’.

___________________________________________

The second title in the Red Antigone Series, is:

Red Chartist

The Complete Annotated Works ofHelen Macfarlane and her Translation of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto

(as published in the Chartist periodicals, The Democrat Review of British and Foreign Politics, History and Literature, the Red Republican, the Friend of the People, and Reynolds News.)

Amazon Link. This title is a paperback, NOT available as an ebook. The content can found, however, in the following book published by Unkant in 2014, now re-issued by BPC as an ebook print replica.

Red Republican

The Complete Annotated Works ofHelen Macfarlane and her Translation of Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto by KarlMarx

__________________________________________

1839: The Chartist Insurrection

David Black and Chris Ford (with a foreword by John McDonnell MP), originally published as a paperback by the late and lamented Unkant Publishing, London in 2012, has now been re-issued by BPC Publishing as a KDP Ebook.

REVIEWS of 1839

Ben Watson, blurb-on-the back:

‘In retrieving the suppressed history of the Chartist Insurrection, David Black and Chris Ford have produced a revolutionary handbook.’

Dan La Botz, New Politics

Black and Ford have written a fast-paced, narrative history of the 1839 Insurrection, filled with thumbnail sketches of the Chartist movement’s major figures, descriptions of the most important Chartist organizations and their politics in brief, excerpts from contemporary speeches, and parliamentary debates, and wonderful descriptions of the movement’s rise, growth, and spread throughout Britain. All of this is based on the most masterful command of the sources: newspapers, parliamentary records, memoirs, private papers, and all of the secondary literature. They tell their story in the most straightforward way but at a breathtaking clip that contributes to the sense of the excitement of the movement and its culmination in the insurrection.”

Stephen Roberts, People’s Charter

I read this book in one sitting as I sheltered from the pouring rain at Bodnant Gardens in North Wales. Based on a wide range of secondary sources and easy to read, it provided a welcome way of spending a few hours whilst waiting for the weather to clear (it didn’t!). The authors tell the story of a year when they assert the conditions for a working class revolution existed. Their account, almost entirely based on such secondary sources as the studies of the Newport Rising by David Jones and Ivor Wilks (but noticeably omitting recent books by Malcolm Chase and Paul Pickering) cannot be said to add to the scholarship, but is full of vigour and engagement. Black and Ford see Chartism in 1839 as ‘a mass working class democratic movement with revolutionary and socialist tendencies’. So this is very much a political account from an avowedly Marxist stance. For the authors a hero of the Chartist story emerges … George Julian Harney. And rightly so: Harney should be a hero to us all.”

R. Reddebrek, Goodreads

A very detailed and readable account of the early Chartist movement, its origins the personalities that came to dominate it and the events that spurred it on to physical force demonstrations culminating in the attempted insurrection in Southern Wales. It also comes with two appendixes that add further context to the time and give a voice to some of the Chartist leaders.

Sharon Borthwick, Unkant Blog, June 26, 2012

This was an exciting time… Dave Black and Chris Ford bring this time alive with this thoroughly researched book which includes many first hand accounts of meetings, battles and the colourful protagonists, many of who fully supported ‘ulterior measures’ in other words arming themselves, should parliament reject the petition for universal male suffrage which really they knew was a foregone conclusion…

This is a period soaked both in romance and horror and our heroes are both romantic and practical. The young George Julian Harney is just 21 when he joins the National Union of the Working Classes. He has been schooled on The Pilgrims Progress, Robinson Crusoe, The Castle of Otranto and the Sorrows of Young Werther. He sports a Jacobean red cap, which he likes to pass onto the heads of pretty young women who favour him with their singing binnies. He was a dogged agitator who travelled extensively to spread the Chartist message…

The momentum is all towards the final battles of 1839 when thousands are amassing in Wales and the North. Harney is finally furious with London as in the North strikes had begun, Manchester succeeding in closing 12 mills, the colliers of Northumberland downing tools. In Newport 6,000 men marched on Westgate but their leader has fled.

Some have lost their lives and many are imprisoned. Dr William Price escapes to Paris where he hangs out with the poet Heinrich Heine. We get glimpses of other characters. We don’t know much about him but that there was a £100 reward on his head, but we are glad that Dai the Tinker has escaped.

James Heartfield, Spiked Online, June 2012

David Black and Chris Ford’s account of the Chartist uprising of 1839 is also written in part to save these agitators from the condescending judgement of an Althusserian, in this case Gareth Stedman-Jones, whose ‘fear of agency’ cannot recognise Chartism’s self-conscious attempt to overthrow ‘old Corruption’. 1839: The Chartist Insurrection is altogether a more rewarding read than Rancière’s for its unapologetic focus on people who are making their own history. Black and Ford make the case that the earlier 1839 uprising came closer to overthrowing the existing order than the later challenge of 1848. They situate the movement in the disappointment of the Reform Act of 1832 that gave the vote to middle- class property owners, but not to the working men who protested alongside them.

Black and Ford make a good case that, though the technology they worked with was not for the most part industrial, the core of the Chartist movement was much more than an outgrowth of radicalism. Of course, it was true that their Charter was a series of democratic demands – adult male suffrage, annual elections, paid Members of Parliament. On the other hand, popular among them was Gracchus Babeuf’s argument that the democratic revolutions in America and France left ‘the institutions of property’ intact as ‘germs of the social evil to ripen in the womb of time’. The common ambition among the Welsh miners that the owners be made to work their own mines tells us that their struggle for democracy was indeed mixed up with a class struggle between owners and hands.

As the authors show, the movement argued hard about how far it should go if its great petition, the Charter, on presentation to parliament, should be refused – as it was. The Chartist Convention, a national organisation with elected delegates, debated the use of ‘Ulterior Measures’ in that case.

George Julian Harney – anticipating modern Sinn Fein’s slogan ‘an armalite in one hand and a ballot paper in the other’ by 150 years – called on his audience to carry ‘a musket in one hand and a petition in the other’. Threatened with prosecution, many in the audience testified that he had in fact said ‘a biscuit in one hand…’. Arguing for the Ulterior Measures, Feargus O’Connor promised that ‘it would be a war of capital against labour, and capitalists would soon find out that labour was the only real capital in the world’.

Still, Black and Ford do not flatter the Chartists unduly, nor make them into cartoon heroes. All the weaknesses of the organisation are confronted here. Throughout the summer of 1839, there were a number of protests in towns across the north of England, notably Newcastle, and in Wales and Scotland, while many smaller groups took up the call to arm themselves. The planned general strike, or sacred month, though, was poorly executed and patchily observed. In some confusion and disarray, the Convention voted to dissolve itself after a number of setbacks.

As it turned out, the leaders’ retreat only opened the floodgates of a movement that was determined to fight on. Black and Ford tell the story of General Napier, who led the militia against the Chartists, though he was himself sympathetic to their cause, if not their methods. On 6 August 1839, Napier wrote: ‘The plot thickens. Meetings increase and are so violent, and arms so abound, I know not what to think. The Duke of Portland tells me that there is no doubt of an intended general rising.’ But Napier’s judgement is compelling: ‘Fools! We have the physical force, not they.’

Black and Ford tell a heartwrenching story of attempted insurrections in Bradford, Newcastle and, most pointedly, in Newport in south Wales, where the movement came to a head. The insurrection was led by the tragic figure of John Frost, who himself was hoping to dampen the movement down, explaining at his trial that ‘so far from leading the working men of south Wales, it was they who led me, they asked me to go with them, and I was not disposed to throw them aside’. Though the Chartists did succeed in taking the streets and the Westgate, their superior numbers were not enough to beat the special constabulary’s better organisation.

All over England, there were risings that failed to meet up, followed by suppression of the movement and a witch-hunt of the organisers. Some escaped, like Devyr, while John Frost was caught and tried – and would have been hanged but that the sentence was commuted to transportation (itself a sign that the authorities feared worse if they killed him). George Julian Harney concluded that ‘organisation is the next thing to be looked into.’

Adam Buick, Socialist Standard, September 2012

The insurrectionary element in the Chartist movement has fascinated left-wing historians who see in it a frustrated revolutionary potential from which a modern vanguard can learn lessons.

Adding to this literature is a new history of the Chartist insurrectionaries of 1839 by David Black and Chris Ford (1839 –The Chartist Insurrection, London, Unkant Publishing, 2012, £10.99). It is a compelling read, telling the story of Chartism through the experiences of George Julian Harney and other ‘firebrand’ Chartist leaders such as Dr. John Taylor and examining the ill-fated Newport Rising of 1839. The authors provide a vivid account of the revolutionary potential that had built up in Britain by the late 1830s, culminating in the aborted rising at Newport in which several Chartists were killed.,

The authors seem disappointed at what they see as the paucity of revolutionary leadership within the Chartist movement. The proposed general strike in support of the Charter is regarded as a failed revolutionary opportunity because Feargus O’Connor refused to see it as a chance for the “revolutionary seizure of power.” Black and Ford argue that “the strike had an inexorable revolutionary logic: with no strike fund to draw on, the people would have to violate bourgeois property rights in order to eat” (pp.88-9). But most Chartists did not want a revolutionary seizure of power; they wanted an extension of the vote backed by the threat that if it was not granted then ‘force’might follow. Chartist leaders such as O’Connor did not want a showdown with the state via a general strike because he knew that the likely consequence would be defeat.,,

The authors suggest that Chartism was neither the tail end of radicalism nor the forerunner of socialism. But it contained plenty of the old in with the new. In their words, “In 1839 the ideas of Thomas Paine stood in dialogue with the socialistic ideas of Thomas Spence, Robert Owen,“`

A short ‘video of the book’ on Youtube

____________________________________________

LSD UNDERGROUND: Operation Julie, the Microdot Gang and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love by David Black PAPERBACK – 21 Mar. 2022

___________________________________________