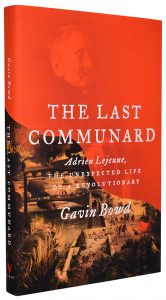

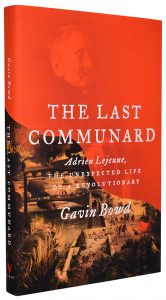

The Last Communard: Adrien Lejeune, the Unexpected Life of a Revolutionary by Gavin Bowd. (Verso, ISBN 9781784782856).

David Black

(May 2022)

Adrien Lejeune’s life story begins with his birth in the Paris of Louis Philippe’s ‘July Monarchy’ in 1847 and ends with his death in Soviet Siberia in 1942. He was, successively, a fighter in the Paris Commune, a socialist and Moscow-line communist. Gavin Bowd, having excavated the historical records, says that ‘the way his life and story have been appropriated, sold and retold is as important as the action he took on the streets in 1871.’

Lejeune was born on 3 June 1847, to a barrel-maker and a seamstress in Bagnolet, a leafy hamlet just beyond the city walls of Paris. By the age of twenty Lejeune had gained employment as a herbalist in a pharmacy on the Paris boulevards. Having joined the Republican Association of Freethinkers, Lejeune soon became notorious in the eyes of his neighbours in Bagnolet, which at the time was a bastion of conservatism. Under Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte’s regime, which was supported by a reactionary Catholic Church, all protest marches and meetings of socialists were forbidden. The Freethinkers were restricted to organising mutual aid, especially for funerals. But funerals for freethinkers often turned into popular demonstrations against the Empire, culminating in cries of ‘Vive la République démocratique et sociale!’

Between 1850 and 1870 the population of Paris doubled to two million, with nearly half a million proletarians employed mostly in small and medium-sized workshops. 30,000 were organised by Workers’ Societies linked to the First International co-founded by Karl Marx.

Louis Bonaparte doomed his empire when, in July 1870, he declared war on Prussia. Two months later he was taken prisoner by the Prussians at the Battle of Sedan. After a bloodless popular uprising in Paris, a provisional Government of National Defence was formed. Headed by the constitutional monarchist, Adolphe Thiers, it was essentially a ‘republic without republicans’.

The new government formed a 200,000-strong National Guard as a defence of the city against the German siege. Adrien Lejuene joined the National Guard, 2nd Company, 28th Battalion and rose to the rank of sergeant. The siege dragged on through the freezing winter of 1870-71. As food supplies ran out, poorer Parisians were reduced to eating rats and the city’s zoo animals. While the French army suffered defeat after defeat in the countryside, German artillery bombarded Paris.

In January 1871, the new government capitulated and sued for peace. Under the terms of an armistice, Thiers agreed to cede the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine to the new German Empire, promised to pay a 5 billion francs war indemnity and granted the German army a victory parade on the streets of Paris on 17 February. As this latter spectacle induced a silent rage amongst the Parisians, some 200,000 of the city’s better-off residents began an exodus to the countryside in fear of what was to come next.

As the rank and file of the National Guard became increasing radicalised, the provisional government ordered that its cannons be seized and transferred to Versailles. On the morning of 18 March 1871, Versaillais troops arrived at the Butte de Montmartre, a strategic hill overlooking the city, to remove the cannons. The alarm was raised by the Parisian milkmaids, and National Guardsmen – Adrien Lejeune among them – rushed to the scene to protect the cannons. As hostile crowds agitated by the Blanquist Left mobilised, mutinous troops refused to fire on them. The generals Lecomte and Clement-Thomas were captured and summarily executed by their own men. The Paris Commune was proclaimed the same day. On 26 March, representatives of the Commune were elected by the citizens of Paris. Thiers’ government decamped from Paris to the relative safety of the palace of Versailles, 17 kilometres from the city.

In the nine weeks of the Commune’s existence, the standing army was abolished along with conscription; control of the schools by the Catholic clergy was replaced by a new system of free compulsory, secular education for all children, including girls; and far-reaching reforms enacted what workers had long demanded, such as the establishment of workers’ cooperatives and restriction of hours.

Adrien Lejeune divided his time between his home in Bagnolet and his National Guard base at the mairie (town hall) of the 20th arrondissement. In what was now a civil war, rural France was now ‘enemy-held territory’. Military efforts to break out of Paris foundered as Thiers, with help from German Chancellor Bismarck, shored up the Versaillais army.

On 21 May 1871, General MacMahon’s Versaillais army entered the city and what became known as the Bloody Week began. During the fighting, the Communards killed or wounded thousands of the invading Versaillais soldiers and torched a number of buildings including the Tuileries Palace and the Hotel de Ville. The pétroleuses (female incendiaries) were blamed for many of burnings by the bourgeois press, but the instances were exaggerated to detract from the achievements of feminists and working-class women communards. In conquering the city the Versaillais army massacred at least 10,000 Communards, including those taken prisoner. 40,000 people were arrested, Lejeune among them.

Gavin Bowd’s research into the fate of Lejeune following his arrest by the Versaillais at the end of the ‘Bloody Week’ on 28 May makes it clear ‘that the reality of Communard Lejeune lends itself with difficulty to the typical Communist hagiography’. In later accounts given by Lejeune and relayed through Communist presses, when the Versaillais assaulted the last bastions of the Commune Lejuene was among those who fought ‘barricade by barricade’ until the final defeat. This however, does not quite square with the defence he offered at his trial in February 1872. Lejeune in fact tried to save himself from incarceration and possible execution by claiming that his daily trips from Bagnolet to the 20th arrondissement had nothing to do with his known extremist politics or armed service for the Commune. He further claimed that his enrolment in the National Guard in the days of the Thiers government did not involve remaining in it to fight for the Commune. The prosecution couldn’t find any witnesses to Lejeune’s alleged military actions, but as numerous local Bagnolet croquants were called to testify that he was an extremist and an infidel, his defence wouldn’t wash with the court and he was sentenced to five years imprisonment. Here again Bowd finds it necessary to challenge later Communist myth-making. For contrary to various accounts Lejeune was not transported to New Caledonia along with the Communard leaders who were spared the death sentence. Rather, Lejeune was put on a prison ship, then transferred to a prison-fortress off the coast of Brittany. Lejeune showed none of the defiance in court of, for example, Louise Michel, who declared to the 6th Conseil de Guerre:

‘I don’t want to defend myself, I don’t want to be defended; I belong entirely to the social revolution and I declare I accept responsibility for all my acts. I accept it entirely and without restrictions’.

Michel was proud that she had offered to assassinate Thiers and burn down parts of Paris. Probably because she was a woman she was not executed, but deported to New Caledonia. Théophile Ferré, as head of the revolutionary police, had sent Georges Darboy, the archbishop of Paris and five other clerics to the firing squad in retaliation for executions by the Versaillais army of Communard prisoners. Ferré declared before his judges:

‘A member of the Paris Commune, I am in the hands of those who defeated it; if they want my head, let them take it! Never will I save my life through cowardice. Free I have lived, and free I will die! I entrust to the future my memory and my vengeance’.

Ferré was executed by firing squad.

It is certain the Adrien Lejeune did fight for the Commune, but his role was not as heroic as told in the legend later promoted by the Communists. During the German siege he was a member of the National Guard, but after the armistice with Germany he handed in his rifle. When the Commune was proclaimed, his role seems to have been restricted to working in the food supply service at the mairie (town hall) of the 20th arrondissement. He did this work until the start of the Bloody Week, when he decided to get out of Paris. He was then arrested at the gates of Paris by the National Guard, who proposed that he resume his service, otherwise he would stay in prison and might be considered a traitor. Lejuene re-joined the Guard, and it seems he fought bravely until 28 May, as he himself testified.

According to Bowd, ‘The records of Lejeune’s revolutionary acts are as mixed as the rest of his life, combining idealism, myth-making and all-too-human frailty. Despite his very modest contribution, the legacy of the Paris Commune would dictate his next seventy years.’

Very little is known about Lejeune’s life in the decades following his release in 1876. In 1871, the Commune’s representative for the 20th Arrondissement had been Edouard Vaillant, a Blanquist who later became a leader of the Unified Socialist Party (SFIO) along with Jean Jaurès and Jules Guesde. Lejeune joined the SFIO in 1905. In 1917, according to a commemorative article in the Communist daily L’Humanité in 1971, he ‘greeted with enthusiasm the socialist October Revolution which meant the triumph of the Commune’s ideas in one sixth of the globe’. In 1922, now aged seventy-five, Lejeune joined the newly-established Communist Party of France (PCF).

In 1928, the Central Committee of the PCF asked the Comintern’s Red Aid International if it could take care of old Communards who were living in France in ‘a very bad situation’. In 1930, Lejeune, whose wife had died a few years earlier, decided to emigrate to Russia and donate his savings. He handed 4,626 francs of annuity to L’Humanité, on condition that the paper ensured him an annual income corresponding to that yielded by his securities. He also donated to the Red Aid organisation.

The octogenarian Lejeune took up residence in Moscow at the Home for Old Revolutionaries. L’Humanité endeavoured to keep him supplied with hampers of wine, chocolate and coffee. Lejeune enjoyed his stay at the home, because other old comrades spoke French and the food was good. But, after 1936, as Lejeune’s health declined, he found himself thrown from one institution to another and neglected by Red Aid. Fortunately for Lejeune, he came under the protection of André Marty, secretary of the Comintern in France and political commissar of the International Brigades in Spain. Marty, in correspondence with Comintern leaders, complained that those responsible for the welfare of the man who was now the last surviving fighter of the Paris Commune were behaving as if they were doing him a favour, rather than the other way round.

According to Marty, when on 15 May 1940 Lejeune learned that the Germans had once again defeated the French at Sedan, he commented:

‘Sedan, so it’s starting all over again? So they still have their Bazaines and MacMahons? Yes, if MacMahon holed up at Sedan, it was because he was afraid of us, because he was afraid of Paris, because he was afraid of answering to the people of France, much more than of the Prussians’.

When Lejeune learned that the Germans had just entered Paris, he sat up in bed, despite his ninety-four years, and exclaimed:

‘It can’t be true. Paris, I must see Paris freed from the brutes and bandits who are sullying it! To see Paris again, our beautiful Paris cleansed forever of fascists and traitors!’

Marty noted angrily that an official of Red Aid, after visiting Lejeune, wrote ‘a schematic, lifeless text, full of clichés plus a quotation from Marx’, and signed it Adrien Lejeune. ‘Not a single French militant will believe it to be by Lejeune’, he added. Marty proposed instead an interview under the title ‘The Communard Who Saw Three Wars’, containing ‘only Lejeune’s opinions, tidied up, of course, but very lively and very relevant to today’.

In July 1941, the Stalin-Hitler Pact was abruptly terminated by Hitler. As the Nazis approached Moscow, Lejeune was evacuated to Peredelkino, a village of dachas, south-west of Moscow. Here, he had as company disabled Spanish Civil War veterans, and a French-speaking Bulgarian exile, Adela Nikolova, who had been assigned by the NKVD as Lejeune’s carer. Nikolova complained to Marty:

‘I cannot remain silent about our arrival the day before yesterday. Our reception was rather difficult. From the very first minute I felt a very wounding atmosphere for us. To receive us like that is incomprehensible. We were greeted like beggars asking for charity, and this state of affairs continues. I hope, dear comrade, that the matter will be sorted out and that I will be able to organise our comrade’s life properly. Our collective has been outraged by the administration’s way of doing things. From my letter you will appreciate how angry I am’.

Again, Marty intervened on Lejeune’s behalf, which resulted in an improvement of the exiles’ conditions at the Peredelkino hospital. In October 1941 as the Nazi threat to Moscow worsened and a state of siege was declared, Lejeune, Nikolova and other exiles were evacuated to Novosibirsk in Siberia, 2,000 miles east. For the 94-year old Lejeune the journey was arduous and life-threatening. In the middle of the freezing Siberian winter, Lejeune’s health worsened despite the care of the ever-loyal Nikolova. In the second week of January 1942, Adrien Lejeune died. He was buried in Novosibirsk. The guard of honour was made up of militants of the Party, the Communist Youth, commanders and commissars of the Red Army, and delegations of Stakhanovites from the factories.

Bowd points out that in the Second World War, the vision of the Commune changed significantly among the French Communists. The image of the Commune, as a proletarian revolution, gave way to one of patriotic resistance to the German occupiers and their collaborators. Bowd writes:

In May 1942, the underground L’Humanité declared, with more than a soupçon of “frenzied chauvinism”: “French patriots, unite and take action against the Boches and their lackeys…” For the Nazis, there was nothing more fearsome than “patriotic resistance to their oppression, to the traitors of Vichy, Pétain, Laval, Darlan and Co…” The Paris Commune was the revolt of the People against the traitors; the people of Paris betrayed and sold; Paris handed over to the Prussians; the Prussians in Paris; Bismarck and Thiers united against the Commune; collaborators of yesterday and today.

What was not stressed by the Communists was that they had long held to the position that the defeat of the working class in the Commune had come about because the French working class lacked a nationally organised Communist Party capable of co-ordination, directing and indeed dominating the movement. They had milked the writings on the Commune of Marx and Engels as well as Lenin’s writings on Marx on the Commune. But they had then added a deadly Stalinist twist. Under Stalin the ‘Leninist’ position of ‘democratic centralism’ was adapted to employ centralised bureaucratic terror against anyone who questioned his policies, and the vision of the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ was perverted into the reality of dictatorship over the proletariat.

The actual Paris Commune was no one-party state. Its version of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat included a wide range of republican tendencies, including Proudhonists, Blanquists, anarchists, feminists, freemasons and Marxists. Marx was certainly aware of the Commune leaders’ shortcomings, such as the failure to seize the money in the Bank of Paris and march on Versailles. Privately Marx criticised the Commune leadership for ruling out any attempt to negotiate a compromise with the bourgeoisie in order to have a democratic republic in which class struggle could take place without violence.

The uses and abuses of the Lejeune legend and the legacy of the Commune carried on through the post-World War Two period. In China in early 1967 worker unrest led briefly to the replacement of the party-run administration by the Shanghai People’s Commune which – to the alarm of Mao Zedong – looked back to the dictatorship of the proletariat as exercised by the Paris Commune.

In France itself, for the Situationists, who played an important catalyst role in the May/June revolt of 1968, the Commune, in Bowd’s words ‘anticipated a new form of society that would be ‘realised art’. For Guy Debord and the Situationists:

‘…they practised a “revolutionary urbanism,” attacking on the ground the petrified signs of the dominant organisation of daily life, recognising social space in political terms, refusing to accept that a monument such as the column on the Place Vendôme – a symbol of Napoleonic militarism – could be neutral or innocent’.

In 1971, the centenary year of the Commune, the PCF, in an effort to restore good relations with the CPSU (which had been stretched by the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968) arranged for Lejeune’s ashes to be brought from Siberia and buried at the Mur des Fédérés in Père-Lachaise cemetery, next to the mass graves of murdered Communards. The PCF event drew tens of thousands, but the centenary also saw large rallies by Trotskyists, and by Maoists who saw the PCF’s initiatives as opportunist and class collaborationist. The French anarchists, for their part, insisted that the Communard most worthy of celebration had been Louise Michel, whose politics were quite at odds with later ‘Leninisms’.

On 10 November 1989, the day after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Gavin Bowd, member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, went for a walk in Paris. He writes:

‘I tried to clear my head of the cataclysmic news of the previous day and repaired to one of my favourite places for solitary contemplation in Paris, the cemetery of Père-Lachaise. Here I wandered among dead leaves and neglected tombs, until I arrived at the corner in the south-east of the cemetery called Le Mur des Fédérés’.

Bowd discovered that day the tomb of Adrien Lejeune, which led to him writing this book. What he found most interesting about Lejeune was:

‘…his real and imagined life, with its convictions, friendships, moments of cowardice, half-truths, lies, shady corners and banalities, a story of property and theft at every level; the manipulation of memory and the (largely consensual) instrumentalisation of an individual who became a ‘relic’ of a cause; the randomness, the pathos and the cruelty of History. It seems that, much more than any novel, the documents and testimonies, swarming with contradictions and silences, constitute in themselves a historical drama and answer at least a few of the questions that a little black marble grave had raised in my mind on the morning of 10 November 1989’.

For Marxisant orthodoxy in the 20th century the Paris Commune, lacking centralised unity and strategy, was history’s ‘rehearsal’ for the Russian Revolution. But if the ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’ has any meaning for today then the legacy of the Communards rises in many respects above that of ‘Bolshevik Leninism’. The Situationists’ Theses on the Paris Commune, written in 1962, whilst recognising the Commune’s obvious lack of a ‘coherent organizational structure’ pointed out that the problem of political structures had turned out to be ‘far more complex to us today than the would-be heirs of the Bolshevik-type structure claim it to be’. Rather than labelling the Commune just as ‘an outmoded example of revolutionary primitivism’, revolutionaries should examine it ‘as a positive experiment whose whole truth has yet to be rediscovered and fulfilled’. They still should.

This article first appeared in the International Marxist-Humanist

(January 2022)

(January 2022)