By David Black

Rise like Lions after slumber — In unvanquishable number — Shake your chains to earth like dew — Which in sleep had fallen on you — Ye are many – they are few. (Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1819)

On 6 January 2021, Donald Trump’s conspiracy to overturn his election defeat made insurrection respectable again – at least among his armed-and-dangerous GOP supporters. The ongoing assaults on liberal democracy – which are by no means restricted to the USA — pose a dilemma for the Left. The alternative, as propounded by the liberal media, is resurgent neoliberalism, even though its representatives seem prepared to dismantle everything liberal democracy is supposed to stand for: freedom of speech, union rights, control of price-fixing monopolies, protection of the environment, social services, etc.

Perhaps it is time to re-evaluate the idea of insurrection from a Left perspective.

The Coming Insurrection, a celebrated tome written by a French collective, pronounced in 2007, ‘Everyone agrees that things can only get worse.’ The ‘Everyone’ certainly now includes the prevailing political parties, who now have only feeblest notion of what might be ‘better’ as opposed to worse. The abjectivity is universal in Western Europe, especially in Britain. An article by Jörg Schindler in Der Spiegel, 18 April, reports:

‘Food shortages, moldy apartments, a lack of medical workers: The United Kingdom is facing a perfect storm of struggle, and millions are sliding into poverty. There is little to suggest that improvement will come anytime soon.’

Schindler quotes a striking nurse he met in Oxford:

‘”There’s something rotten here,” she says. “Nothing is as it used to be.” The longer she speaks, the more it seems she’s actually talking about the entire country. seeking its salvation in the very financial industry that collapsed so spectacularly 15 years ago, creating a situation in which billions were squandered…. And now, it seems as though it has dialed 999 and is waiting in vain for the paramedics to show up.’

The Financial Times of 28 June reported a poll by the New Britain Project which shows that nearly three-fifths of voters say ‘nothing in Britain works anymore’ and four-fifths don’t believe politicians have the ability to solve the UK’s biggest issues.

Kier Starmer’s mantra of ‘stability, order and security’ is chanted over the bonfire of the ‘pledges’ he made to get elected as party leader. In the most glaring example, Starmer, having promised to renationalise the failing, corrupt water utilities that are polluting our rivers and coastline, he has backtracked and promised the ‘market’ that the looters will remain in control.

The call of The Coming Insurrection, which seemed extreme back in 2007, now looks quite reasonable:

‘It’s useless to wait—for a breakthrough, for the revolution, the nuclear apocalypse or a social movement. To go on waiting is madness. The catastrophe is not coming, it is here. We are already situated within the collapse of a civilization. It is within this reality that we must choose sides.’

In the post-2008 Crash period, with the rise of Left populism internationally, the word ‘insurrection’ was in the air; which was why we, in 2012, called our book, 1839: The Chartist Insurrection, Our focus was expressed in Ben Watson’s, blurb: ‘In retrieving the suppressed history of the Chartist Insurrection, David Black and Chris Ford have produced a revolutionary handbook.’

Member of Parliament, John McDonnell, wrote in the Foreword to 1839:

‘Labour movement historiography has overlaid the Chartist story with the concept of an overwhelmingly, conservative British working class and a solely reformist British Labour Movement. The message has been consistently drilled into us that revolution was and is futile. This book offers another perspective. Revolution in Britain in 1839 was closer than we have been previously taught.’

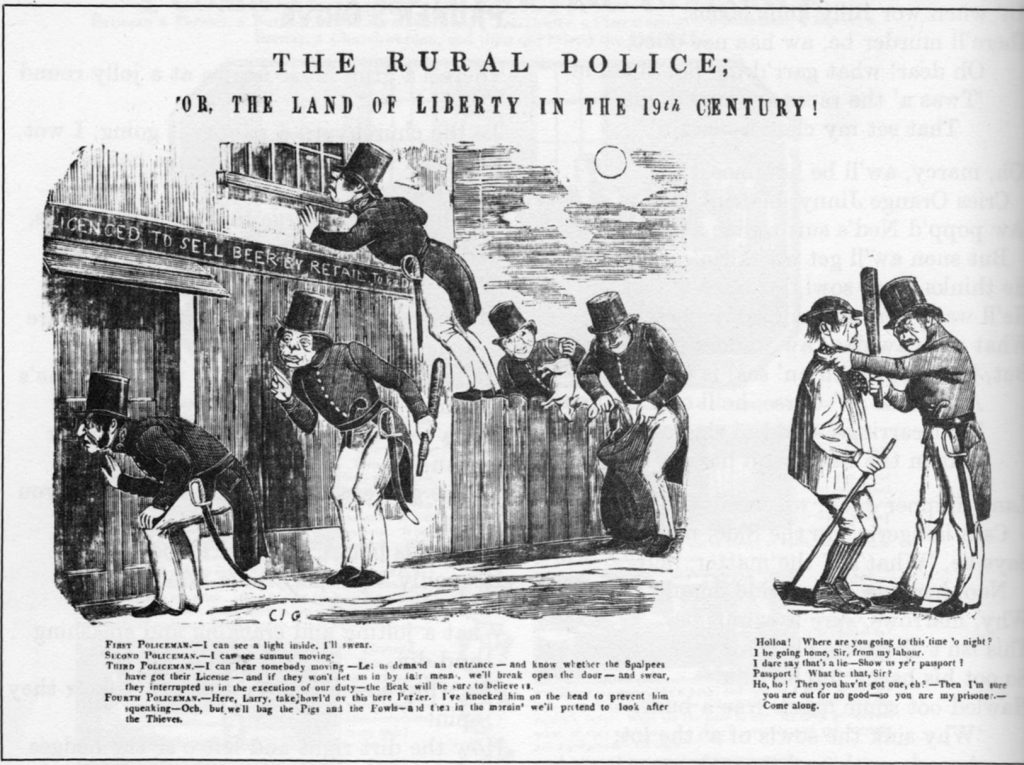

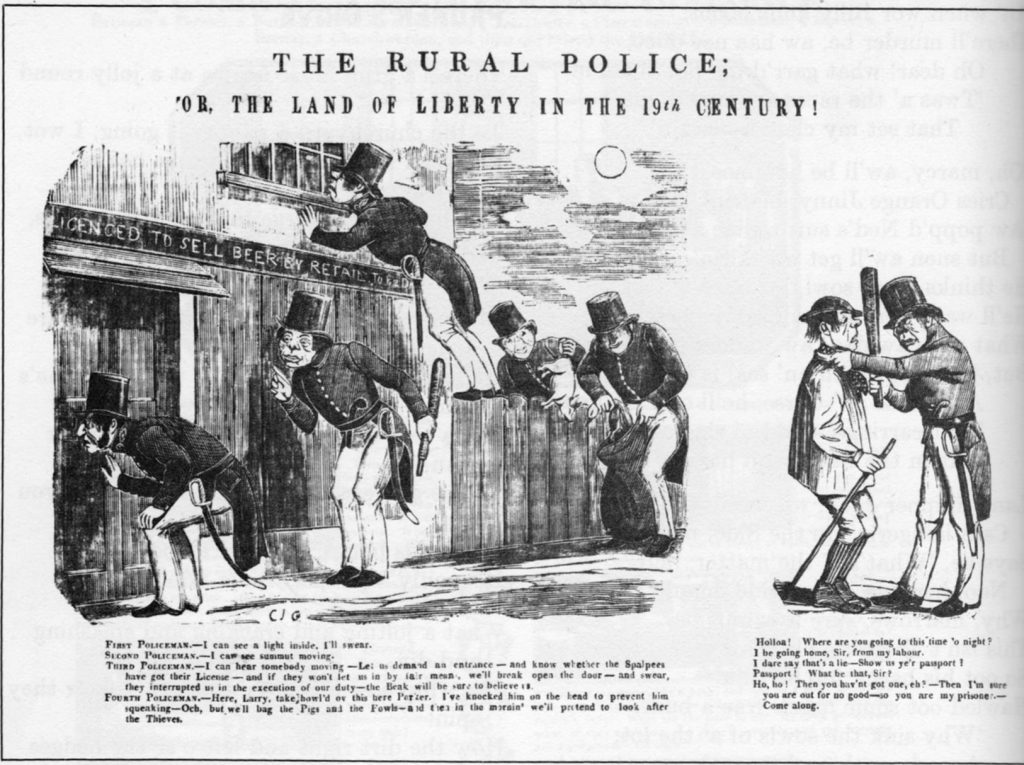

The Chartist National Convention of 1839 discussed various means for furthering the struggle for democracy, one of which was the ‘old constitutional right’ of ‘free men’ to bear arms ‘to defend the laws and constitutional privileges their ancestors bequeathed to them’. Their reasoning was that the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 wouldn’t have happened if the pro-democracy demonstrators had been armed. Of course 200 years later, peaceful protestors are no longer cut to pieces by sabre-wielding gentry-on- horseback. Also, Britain does not a gun-culture. For all intents and purposes, fire arms struggle can be ruled out.

Not so, other ulterior measures. The Chartists discussed and sometimes implemented several measures that today are worth conserving as tactics: withdrawal of money from ‘hostile’ banks; a month-long general strike; torchlight processions; refusal to pay rents, rates, and taxes; boycott of anti-Chartist newspapers; protection of persecuted activists; secret organisation of prohibited political activities, contestation of public spaces, and more. Some of the Chartists’ ulterior measures could rethought for our time. The Citizen’s Advice Bureau, which is hardly revolutionary, offers the following:

‘If you are a domestic (non-business customer), water companies can’t, by law, disconnect or restrict your water supply if you owe them money.’

In 1839, the Chartist masses were fighting for democratic representation as a means to address economic and social grievances. Today it is evident that means and ends cannot be separated.

Unkant Publishing went out of business in 2015, leaving the book ‘homeless’ and out-of-print (although it can still be obtained from some online booksellers). One of the aims of this blog is to help the book find a new publisher.

Review

James Heartfield, Spiked Online

David Black and Chris Ford’s account of the Chartist uprising of 1839 is also written in part to save these agitators from the condescending judgement of an Althusserian, in this case Gareth Stedman-Jones, whose ‘fear of agency’ cannot recognise Chartism’s self-conscious attempt to overthrow ‘old Corruption’. 1839: The Chartist Insurrection is altogether a more rewarding read than Rancière’s for its unapologetic focus on people who are making their own history. Black and Ford make the case that the earlier 1839 uprising came closer to overthrowing the existing order than the later challenge of 1848. They situate the movement in the disappointment of the Reform Act of 1832 that gave the vote to middle- class property owners, but not to the working men who protested alongside them.

Black and Ford make a good case that, though the technology they worked with was not for the most part industrial, the core of the Chartist movement was much more than an outgrowth of radicalism. Of course, it was true that their Charter was a series of democratic demands – adult male suffrage, annual elections, paid Members of Parliament. On the other hand, popular among them was Gracchus Babeuf’s argument that the democratic revolutions in America and France left ‘the institutions of property’ intact as ‘germs of the social evil to ripen in the womb of time’. The common ambition among the Welsh miners that the owners be made to work their own mines tells us that their struggle for democracy was indeed mixed up with a class struggle between owners and hands.

As the authors show, the movement argued hard about how far it should go if its great petition, the Charter, on presentation to parliament, should be refused – as it was. The Chartist Convention, a national organisation with elected delegates, debated the use of ‘Ulterior Measures’ in that case.

George Julian Harney – anticipating modern Sinn Fein’s slogan ‘an armalite in one hand and a ballot paper in the other’ by 150 years – called on his audience to carry ‘a musket in one hand and a petition in the other’. Threatened with prosecution, many in the audience testified that he had in fact said ‘a biscuit in one hand…’. Arguing for the Ulterior Measures, Feargus O’Connor promised that ‘it would be a war of capital against labour, and capitalists would soon find out that labour was the only real capital in the world’.

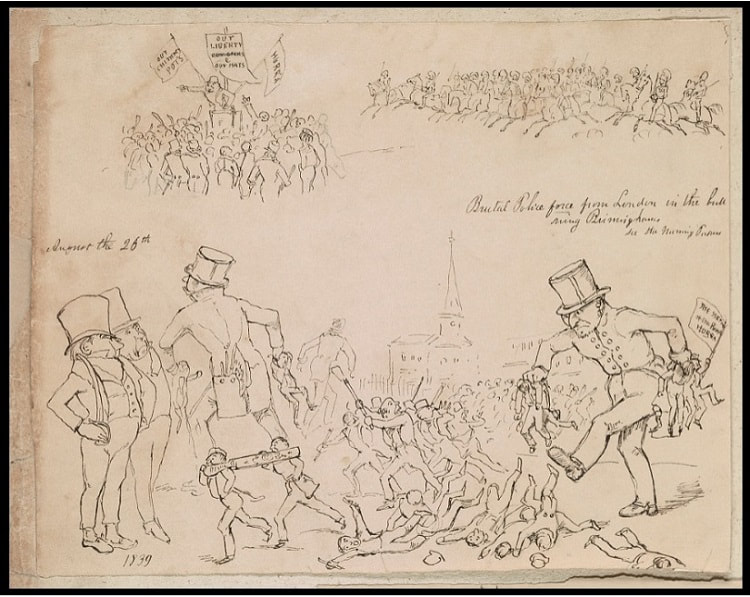

Still, Black and Ford do not flatter the Chartists unduly, nor make them into cartoon heroes. All the weaknesses of the organisation are confronted here. Throughout the summer of 1839, there were a number of protests in towns across the north of England, notably Newcastle, and in Wales and Scotland, while many smaller groups took up the call to arm themselves. The planned general strike, or sacred month, though, was poorly executed and patchily observed. In some confusion and disarray, the Convention voted to dissolve itself after a number of setbacks.

As it turned out, the leaders’ retreat only opened the floodgates of a movement that was determined to fight on. Black and Ford tell the story of General Napier, who led the militia against the Chartists, though he was himself sympathetic to their cause, if not their methods. On 6 August 1839, Napier wrote: ‘The plot thickens. Meetings increase and are so violent, and arms so abound, I know not what to think. The Duke of Portland tells me that there is no doubt of an intended general rising.’ But Napier’s judgement is compelling: ‘Fools! We have the physical force, not they.’

Black and Ford tell a heartwrenching story of attempted insurrections in Bradford, Newcastle and, most pointedly, in Newport in south Wales, where the movement came to a head. The insurrection was led by the tragic figure of John Frost, who himself was hoping to dampen the movement down, explaining at his trial that ‘so far from leading the working men of south Wales, it was they who led me, they asked me to go with them, and I was not disposed to throw them aside’. Though the Chartists did succeed in taking the streets and the Westgate, their superior numbers were not enough to beat the special constabulary’s better organisation.

All over England, there were risings that failed to meet up, followed by suppression of the movement and a witch-hunt of the organisers. Some escaped, like Devyr, while John Frost was caught and tried – and would have been hanged but that the sentence was commuted to transportation (itself a sign that the authorities feared worse if they killed him). George Julian Harney concluded that ‘organisation is the next thing to be looked into.’

June 2012