David Wise

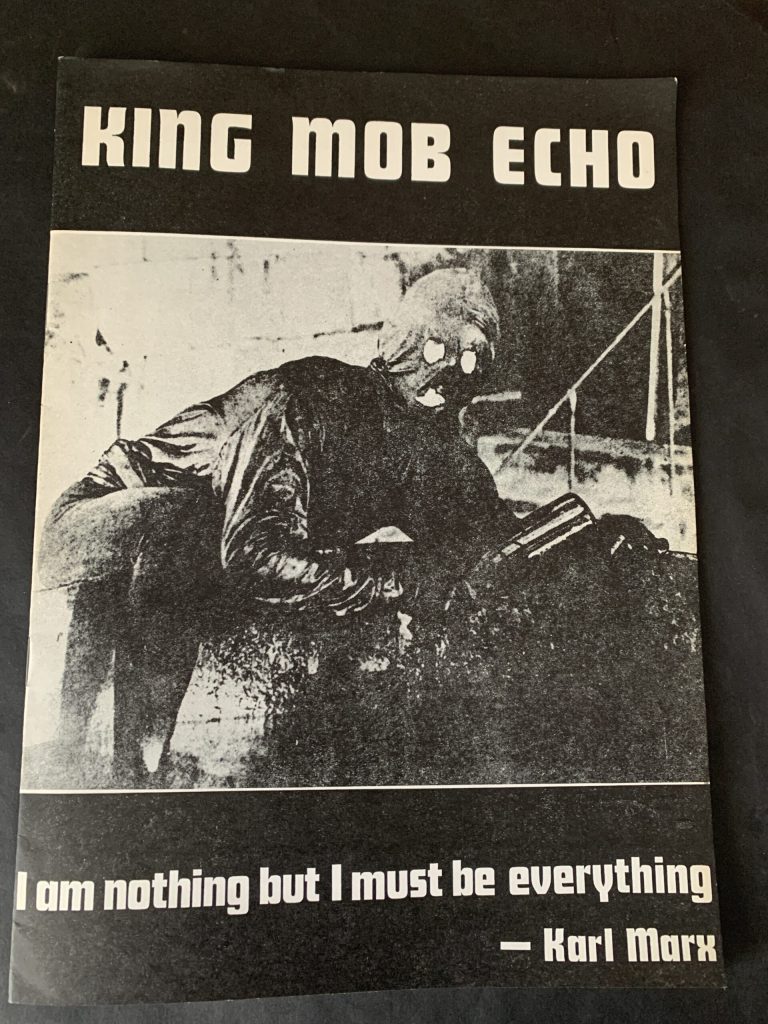

Editor’s note: In response to my review of Eric-John Russell’s translation of Jaime Semprún’s book, A Gallery of Recuperation: On the Merits of Slandering Charlatans, Swindlers and Frauds (first published in 1976 as Précis de récupération: illustre de nombreux exemples tires de l’histoire recente) David Wise, co-founder of King Mob, the English radical group of the late 1960s/early ‘70s, which was connected to Guy Debord and the Situationist International., has contributed the following.

FROM LONDON TO LISBON

I enjoyed reading David Black’s Substack comments on Eric-John Russell’s recent translation and re-publication of Jaime Semprún’s Précis de récupération. Decades ago I found myself in agreement with Semprún’s withering dismissal of post-modernism as represented by so-called thinkers like Michel Foucault, Jean-François Lyotard, Andre Glucksmann, Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. After ‘liberating’ (meaning going beyond monetization rather than ‘thieving’) a fair amount of these authors’ oeuvre from the UK’s ‘nintellectual’ bookshops, I myself, along with other clued-in mates, had had enough of seeing their books stacked up prominently in front of us. These surface commentators, with their endless watering down of the rejuvenating spirit of the May ’68 revolution in France, were being presented as real cutting edge subversive critique; when in truth, the real McCoys couldn’t get a look in with English language publishers.

Although I welcomed Précis de récupération as a breath of fresh air, I was cautious about Semprún’s attacks on Cornelius Castoriadis and ‘Ratgeb’ (Raoul Vaneigem), both of whom once had meaningful connections with Guy Debord. Sadly, mention of English speaking recuperation was absent, as basically the UK, in comparison with much of Europe and even the USA, was backward regarding the explosions of the late 1960s – so much so that the majority of ‘thinkers’ here wouldn’t know what the fek you were talking about. Hardly surprising then that our merry band was defined by our hatred of the “right little/tight little island” Little Englander mentality of both right and left wing (although we never realised that these tendencies were going to have such an abominable outcome decades later, what with Brexit and the like).

In retrospect and on a general level, I think Précis de récupération marked the final moment of Semprún’s hero worship of Debord. After that, Semprún took a different radical path as he morphed into the creator of the very influential ‘group’ cum publisher of Éditions de l’Encyclopédie des Nuisances (‘Nuisances‘ meaning destructive, dangerous substances). On the simplest of levels, Debord and Semprún were very different characters, i.e. Semprún didn’t really fall out with people (at least not in the same way Debord did). I don’t think Guy ever forgave him for walking away, causing Guy to henceforth endlessly obsess about this ‘scally’; finally denouncing him as a ‘mediatique’ in his last ‘book’ Cette Mauvais Reputation. (I remember Michel Prigent – the publisher of Chronos Press and Principia Dialectica in London – not really liking Debord’s final book, although he was somewhat nervous about saying so). Other friends, in France, mainly around Os Cangaceiros, clearly noted that Semprún had been unfairly rubbished as he wasn’t involved with the media and had even gotten rid of films he’d produced and acted in when a youngster.

Around the same time as Précis de récupération was published,Jaime was also involved with radical social struggles erupting in Portugal and then Spain after the death of the fascist dictator General Franco. Practically, he did so in a somewhat clandestine way, in and around a group – if one can call it that – aptly named Los Incontrolados (The Uncontrollables).

First though. something of a detour. The end of the ‘glorious’ late 1960s was somewhat marked world-wide by a ‘collapse’ of its protagonists, ourselves included. Dazed and depressed, overcome with a sense of failure, we were floundering, desperate again to reignite our fiery passions, as well as desperately searching for a wide-ranging and nuanced re-think. Some individuals – rapidly or cautiously but slowly – sold-out, while others destroyed themselves with drink and drugs. Also, there were the suicides, which were really hard to bear as it was often the finest individuals who decided to end it all.

Others fled to other countries. Ex-King Mobber, Phil Meyler, was one such person. After a tumultuous, exhilarating time in the late 60s/early 1970s, journeying between London, Ireland and the USA, Phil seemed to abandon everything and, after sometime desolately moping around in east London, he suddenly upped-sticks and disappeared to Portugal where he found casual paid work teaching English as a foreign language. His first letters to me in London from Lisbon were desolate and harrowing… then, then, then on the 25th of April 1974 the ‘Revolution of the Carnations’ broke out and the streets and work places erupted amidst the ferment in and around the final overthrow of Salazar’s/Caetano’s 50 year old fascist dictatorship. Phil’s letters transformed overnight; becoming absolutely fascinating. Moreover, Phil and I had been best mates throughout the late 1960s; reinforced by the fact we were from similar working class backgrounds, had little money and no prospect of inherited wealth coming our way. Now, whoosh, here was a rejuvenated Phil sending me one stunning letter after another about what was going down on the Iberian Peninsula. In response, I just wanted to get this information out there in the English speaking parts of the globe.

In the following months, frequent visits to Portugal became essential; the country having become a hub for all kinds of radical tendencies, with many rebels from different European countries enthusiastically proclaiming Situationist ideas – amongst other persuasions. Described at the time as ‘revolutionary tourism’, (as against the typically banal, often hated, mass consumer tourism) it was a 24/7 fascinating mix of thought, action, love and alcohol. Already there was an emerging tendency beginning to put an emphasis on the need to update Marx’s critique of value, etc, with clued-in individuals saying the Situationists had missed out on this essential factor, thus implicitly raising the question: ‘what steps do we take from here?’.

The immediate outcome was that Phil put together a book in Portuguese and English entitled, Portugal, The Impossible Revolution. It was a producedby Solidarity (the Castoriadis-inspired off-spring in the UK of Socialisme ou Barbarie). I was able to fund it, as I was earning really good money as a plasterer on building sites, had no family to support and as a squatter I had a rent-free place to live. The book captured the warp and woof of the uprising, that unmistakable, ‘I was there’ dimension, emphasising at times its delightfully crazy essence. Little did we know at the time that Jaime Semprún had also put together a book called La sociale guerre au Portugal, published by Champ Libre in France (the company owned by Debord’s rich friend, Gérard Lebovici (who was murdered in complicated circumstances which I won’t go into here). The book was immediately proclaimed as the finest critique and evaluation of the Portuguese uprising, though to my mind it was touch and go in comparison with Phil’s hands-on unruly passionism, which captured the emotional euphoria of the uprising. As I put down in a notebook at the time:

“I certainly had a memorable New Year in Lisbon in 1976-7. A crowd of us got drunk in a workers’ tasca which ended up with a conga winding through the adjacent streets. It was nearly dawn before the cavorting ceased and then some of us decided to go to the local zoo for some reason even though we knew it would be closed. We went with some vague notice of liberating wild nature as happened during the Paris Commune of 1871. Climbing the fences into the zoo we were in a mood to fraternise directly with the animals on display and proceeded to do so. Although we couldn’t get into the tigers den we certainly were able to stroke the creatures a little as we could the giraffes, etc. But then it was easy to get into the hippopotamuses enclave. A big hippo with such friendly, benign eyes opened its mouth wide and laughingly the assembled drunks dared “the mad Englishman”(Me) to put his head in the hippo’s mouth. Well I did and everybody gasped. BUT THAT WAS IT,OVER AND OUT. Armed police had been called and they immediately came for us and later, we were banned from ever going again into a Portuguese zoo. But the incident had gotten out and about on the alternative grapevine and years later people were still sending me tiny toy hippos with their mouths open. Evidently – in reality – hippos instantly bite heads off……. but how was I supposed to know that???”

More importantly, the atmosphere in Portugal started overlapping with what was happening in Spain after the death of General Franco and the impending demise of the fascist dictatorship. Shortly after returning to London, Phil sent me through the post a small Spanish pamphlet which had knocked him out. It was named, “Manuscrito encontrado en Vitoria” (A Manuscript found in Vitoria). Like Phil, I also thought the pamphlet was terrific.Then he ‘found’ another pamphlet and then another- all with different titles and all anonymous! All we had to go on was the name: Los Incontrolados…. and for the life of us, for what seemed like ages, we simply couldn’t find out the names of the individuals who’d written them. One by one Phil forwarded these pamphlets to me in London and we then decided to translate and publish them. Needless to say our command of the Spanish language wasn’t that good and my twin bro’ Stuart Wise – who did most of the translation – also wasn’t that much better. There again, there was no one around to help us: educationally we were the old notorious 11-Plus failures, not worthy of ‘proper’ education and hampered by the fact our “English” was truly awol (Phil being from Dublin and us from County Durham and Yorkshire). Who could we to turn to? Comatose academics who hadn’t grasped Lautreamont’s pre-Surrealist maxim: ‘The new tremors are running through the atmosphere and all you need is the courage to face them’? Thus, in consequence the book with all its somewhat gobbledygook translatese, Wildcat Spain Encounters Democracy was kind of stillborn!

It’s worth saying here that ‘revolutionary anonymity’ in the mid to late 1970s rapidly seemed to acquire quite a profile, or rather, anti-profile. In a way it had become a principled gesture against the horrendous groundswell of stardom and names in lights which was taking off like never before, as post modernism and its academic parade imbibed the accoutrements of pop culture with the gradual eclipse of the revolutionary spirit of 1968. It was all for the sake of money and more money, preparing the way for today’s kleptocratic rule. For all like us, a name didn’t matter and any pseudonym was just as good as another. It was the hoped-for inspirational content that mattered, mirroring the fact you lived your life in an anti-spectacular, non-touchy/feely way. Thus, that’s how our pamphlets were signed. As for Phil there was another pressing reason; he slightly altered his last name from Meyler to Mailer – a la Norman Mailer the famous contemporary American hipster writer – as the Portuguese state was rapidly becoming hell-bent on getting rid of subversive foreign undesirables.

The town of Vitoria (Victory) in the Spanish Basque country became a brilliant hot spot in the mid-to late 1970s as home to an autonomous worker revolt which was quite astounding in its breadth, hence the nuanced ‘victory’ pun in the subsequent A4 pamphlet by Los Incontrolados. As a consequence, a few years later we discovered that the principal authors of Los Incontrolados were Jaime Semprun and Miguel Amoros. Subsequently, Semprun’s post situationist radical eco-orientation was to have a profound influence on us although contact was kind of ‘in and out ‘and mostly – at a distance. Miguel’s critique of the destructive ultra- commodification of music was contemporaneous with my own pamphlet, The End of Music. Inevitably, Miguel lamented our inadequate Spanish translations. Unbeknown to us, at the same time Miguel Amoros was slowly writing a really fascinating account of their differences with Debord, etc, (much of which has ended up in the web pages of Libcom.org). And finally (for me) I discovered that Jaime was the son of the Spanish/French novelist, Jorge Semprun, whose dissident-communist writings I’d had a lot of respect for in mid 1960s Newcastle. Lo and behold in post- Franco Spain, Jorge, who had been expelled by the underground Spanish Communist Party, had become a literary celebrity, and was set to become Spanish Minister of Culture (!). I was horrified and later gratified to find out that Jaime would have nothing to do with his Dad, having always detested his membership of the Communist Party and no doubt much else besides.

And yes, I’d become nervous of Debord and subsequent “Our Party” Debordism. After our pamphlet on the 1981 riots in the UK, A Summer with a Thousand Julys, was translated into French I was subsequently was invited by Guy Debord to visit him in Champot in the remote French countryside where he was then living. I’d be accompanied by Michel Prigent. But I had to turn the invite down as I knew I’d completely fek-up, especially when I’d hit the booze to calm my nerves. I knew individual sentences in the pamphlet would be picked on and obsessed over (as was the regular pattern) and I didn’t have the character armour to resist this interrogation thus, ‘[a sadder and a wiser man (David Wise) rose the following morn.’

ECO-ACTIVISM V. GREENWASHING

By the late-1980s, Jaime Semprún’s eco critique was getting really cutting edge the more he acknowledged the profundity of the English language description of that devious con and substitute for authentic eco involvement becoming known as ‘greenwashing’. Jaime was also one of the first individuals to call out the duplicitous horrors of a double dealing ‘Nature Bureaucracy’, made up of all the species protection societies and the like. Initially we naïvely thought these bodies were on our side when engaging in actions to genuinely increase and enrich biodiversity, only to find out they were some of the nastiest – forever calling the police on our activities. The realisation of such a truth was shattering both for Jaime and ourselves.

What followed somewhat later for Jaime and Co was radical eco-action on the Larzac Plateau in south west France in the mid-1990s. This also involved the former-Situationist International member, René Riesel, who had played such a significant part in May ’68 in France. At the time I was also getting a lot of fresh comment from other friends involved, again mainly from Os Cangaceiros. Suffice to mention here one amusing incident. There was some kind of festive eco get together in a small town on the Larzac Plateau and stalls were erected. Stalwarts of Éditions de l’Encyclopédie des Nuisances in souped-up militant attire turned up really ready for action against the brutal French police. First though, they had to put together a stall. Most of the activists couldn’t do it as (it seemed) none of them had ever used a hammer or screwdriver (they were so ‘middle class’, or at least ‘middle class’ in practical disposition). In exasperation, Riesel (who by then had become a neo-peasant farmer) jumped in and assembled a stall made up of wooden planks within minutes. Everybody present had a good laugh….. Nonetheless, Nuisances was quickly to acquire a huge influence especially regarding the future French ZADS (Zones a Defendre). And subsequently we might ask: how could the comradely alliances around Earth Uprising and the Sainte-Soline Battle of the Basins of March 2023 have come about without this ‘distant’ history?

One more comment haphazardly comes to mind. Michel Prigent kind of liked Jaime Semprún, though he said to me he didn’t like the way he ‘supported the Unabomber terrorist’ (Ted Kaczynski) in the mid-west United States. As for myself, I balked at the terrorist name tag. Though I didn’t approve of the haphazard parcel bombs and was leery about innocent casualties, I liked some of the Unabomber’s writings.

Ah, but then, slowly but surely on a more general, historical level, a morphing Situationist perspective was disappearing quite rapidly after say, 2015. What was happening? Miguel Amoros was of the opinion that a dreadful counter-revolution was finally taking place especially in English speaking countries. Yes, it certainly feels like that as today you can’t find traces anywhere of the Situationist experience in what now passes contemporary revolutionary critique. As an interesting aside to all this – even though again utterly out of place – the writings of Alèssi Dell’ Umbria really have edge, even though, as far as I know he, also, never mentions the Situationists. I’ve been told this guy, who is from Marseilles, was a fellow traveller of Os Cangaceiros and has written some really interesting tracts around major social upheavals in France over the last 20 years or so. It’s certainly true that his C’est La Guerre. written in the first few months of 2023 is so far the best account of those exhilarating moments. And there is also an excellent tract on the Gilets Jaunes disturbances in Marseilles in 2019. I was asked by Jack-de-Montreuil if I could translate into English Alessi’s recent major theoretical contribution named Antimatrix. I rapidly found out that It was certainly a dense and very interesting text and by my reckoning a relevant update to The Society of the Spectacle without ever mentioning the latter’s existence… But I wonder if my French and background knowledge are really up to it. Whatever, it would be excellent if say, MIT Press Ltd could publish a selection of Dell’Umbria’s writings in English.

Sadly, Jaime Semprún died in 2010 of a cerebral haemorrhage, aged 63. His death was untimely, but in truth his writings in later years had become a lot more sombre and it may be that he found the derailing of his radical eco experiments heart breaking. In something of a final missive Jaime said all he could do now was cultivate his own back garden. We indeed felt something of the same, re broken hearts, even though we had no back – or front – garden to cultivate as we lived in sub-standard social housing. We, on the contrary, had turned our attention to scruffy, gloriously weed-ridden public space with the intention of vastly increasing their inherent bio-diversity. We never asked permission of the powers that be – usually town councils – because we knew we’d be told to fuck off for not possessing requisite qualifications, etc. Constantly under attack from officialdom and the police we nevertheless over the years produced some remarkable spaces which even moronic bureaucrats had to grudgingly admit was the case.

This was especially true of our eco intervention between 2010-17 in the Bradford Canal and Shipley’s ‘Industrial Gorge’ in West Yorkshire – an arena which had obsessed John Ruskin in the late 19th century. That encounter, regarding greenwashing, was a brutal eye opener, as the authorities came for us with no holes barred, deploying thuggery and threats of jail regarding our eco interventions. We also sprayed up on various stone walls in the gorge some relatively recent lucid quotes from Miguel Amoros on the subject of greenwashing, only to find them jet sprayed out a few days later by council goons.(In retrospect I think Miguel knew about these slogans and was pleased we had given them prominence). Also our eco interventions over the last few years on Wormwood Scrubs in West London were somewhat simultaneously explained by ourselves through placards, bird boxes and the like hung high up in trees – many around the subject of ‘suicide capitalism’, which was basically an ecological concept elucidated by Jaime Semprun. A few months ago I could have directed you the reader to our website, The Revolt Against Plenty, where photos alongside texts explained the concept. Then kaput: there was nothing except total wipe-out! The brutal redaction of thewebsite in spring 2023 meant all of this history has now been liquidated along with so much else besides and now can only be accessed via The Wayback Machine archives. Why wasn’t a reason given for such brutal action? Why did absolute silence reign? Finally, I came to the conclusion that basically, it’s a sign of the brutal reaction which is today spreading throughout the world. And if you aren’t rich enough to hire a good lawyer the attitude is you can just fuck off as we can do what we like with you; not forgetting that law centres for those surviving at the sharp end disappeared yonks ago. Left in a catastrophic dilemma, just what is there to do about such fiendish acts when reaction is becoming so omnipotent everywhere and all emancipating hope is rapidly dwindling? It’s beyond heart-breaking.

Dave Wise (together with the inseparable shadow of my twin bro’ Stu’ Wise who is forever and forever by my side).