1839: The Chartist Insurrection by David Black and Chris Ford (with a foreword by John McDonnell MP) was published in 2012, during a time of intensifying social crisis. Ben Watson’s blurb on the back cover captured our intention to write an account of a rebellion from long ago which would inform and inspire readers in the present: ‘In retrieving the suppressed history of the Chartist Insurrection, David Black and Chris Ford have produced a revolutionary handbook.’

During the aftermath of the 2008 Crash the slogan, ‘We are the 99 per cent’, echoed around the world and frightened the rich and powerful. In the Middle East the Arab Spring overthew, or seriously threatened, well-entrenched dictatorships, and throughout Western Europe, anti-capitalist populism was gaining ground. In Greece, the Left, united in the Syriza Coalition, were heading for state power.

In Britain in 2012, David Cameron’s Conservative government was imposing drastic austerity measures. The apparent cancelation of the future along with the immiseration of the present faced no serious challenge from the leadership of the Labour Party, whose dearth of ideas, vision, energy and courage was evident to a new generation of malcontents, especially those radicalised by the massive student protests of 2011. This alienation from Labour’s deadbeat centrism formed the impetus for the unexpected revival of the party’s Left under Jeremy Corbyn. Following the rout of Labour under Ed Miliband in the 2014 General Election, John McDonnell became shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer under Jeremy Corbyn’s new leadership.

Participants in contemporary political events often turn to examining past events for enlightenment. Other ignore or distort them. As Paul Mattick once put it, ‘What one generation learns, a later generation forgets.’ Fifty years after the Chartist uprising of 1839, Sidney and Beatrice Webb of the Fabian Society published a ‘lessons from history’ handbook for a new party of moderate progress within the limits of the law, entitled The History of Trade Unionism. Looking back at the Chartist movement, the Webbs wrote:

‘A general despair of constitutional reform led to the growing supremacy of the “Physical Force” section of the Chartists, and to the insurrectionism of 1839-42. Made respectable by sincerity, devotion, and even heroism in the rank and file, it was disgraced by the fustian of many of its orators and the political and economic quackery of its pretentious and incompetent leaders whose jealousies and intrigues, by successively excluding all the nobler elements, finally brought it to nought.’

The Webbs’ version of the ‘Whig Theory of History’ set the ‘standard’ for writing about Chartism by ‘Labour Historians’ in the 20th century. In contrast, we argue that the ‘excluding all the nobler elements’ was rather their own self-exclusion from the practical problem of a working class that was unfranchised, over-taxed, starved into workhouses, and exploited by landowning aristocrats and industrial capitalists. In researching how the working class radicals and their allies acted after the betrayal of their estwhile Liberal allies we found that many of physical-force leaders had a grasp of intellectual ideas which they attempted to put into practice for the edification of the masses. The Jacobin-inspired propensity for ‘physical force’ – to the point of armed stuggle – was by no means restricted to a few ‘extremists’ and enemies of liberal ‘progress’. George Julian Harney, one the ‘physical force’ leaders in 1839, recalled in later life:

‘When I look back upon the past, when I remember the wrongs and sufferings of the working classes, far from being able to reproach myself with “violence”, I am astonished at my moderation; considering as I do that the wrongs referred to would have satisfied a degree of “violence” far beyond anything my recollection enables me to charge for my own account.’

Unkant Publishing went out of business in 2016, leaving the book homeless and out-of-print (although it can still be obtained from some online booksellers). One of the aims of this blog is to help the book find a new publisher. Over the summer I’ll be posting a few sample chapters. This post features the Foreword contributed by Labour Member of Parliament, John McDonnell MP, who was to become Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer under Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party.

Foreword by John McDonnell MP to 1839: The Chartist Insurrection by David Black and Chris Ford, Unkant Publishing (London:2012)

There is a school of Labour movement historiography that emulates the old Whig theory of British constitutional history. Just as the Whig Theory of History views a succession of constitutional changes over centuries simply as a series of small steps in a linear progression to the perfection of the liberal democratic state (claimed by some as the “end of history”), there have been fellow travellers in Labour History writing, who have seen the individual struggles of groups of peasants and working people over recent centuries as merely the stepping stones on the path to the ultimate goal of the founding of the Labour Party, the TUC and the modern day trade unions.

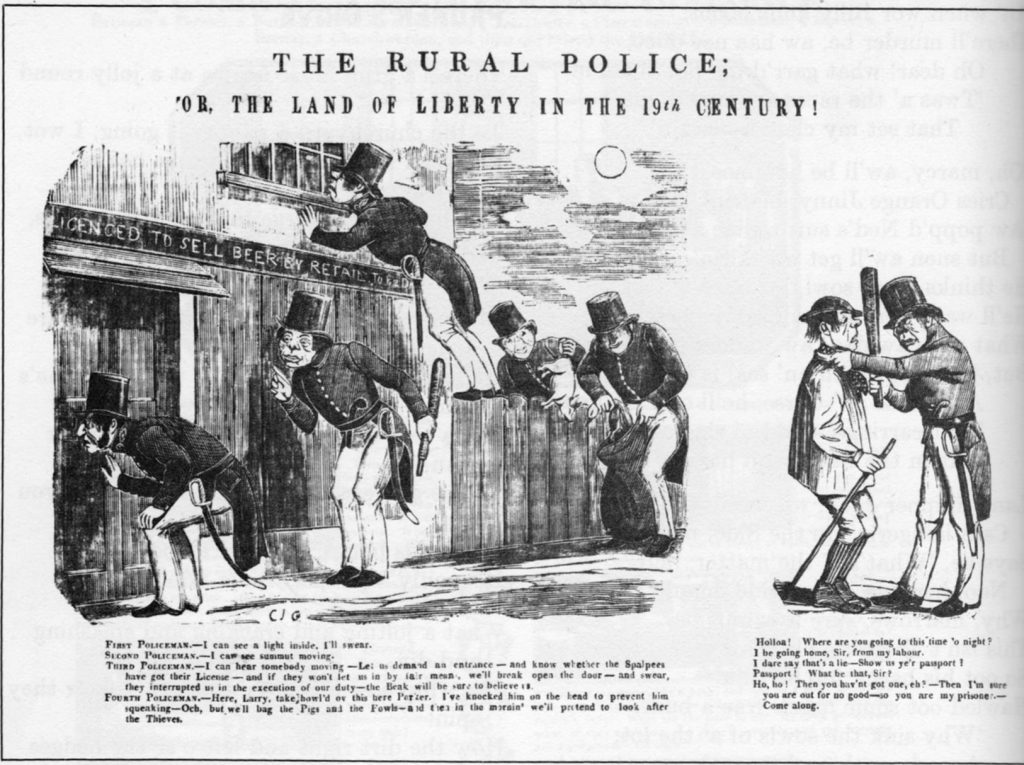

Those elements or key events in Labour movement history that have not conformed to the theory of the ineluctable, evolution of the movement into a party committed to peaceful, constitutional reform have been either written out of history altogether or relegated to mere historical footnotes. Often they are portrayed as deviations at best irrelevant to or, worse still, hindering the progress of effective working class political representation.

Those historical actors or movements that in Britain explored or attempted out on other routes to political change are generally considered condescendingly as primitives or patronisingly as naïve as soon as they ventured down the path of physical force or large scale resistance associated with Revolution rather than Reform.

Consequently in most histories of the British Labour movement the story of the Chartists has focussed on the large scale mobilisations of petitioners, the development of mass-circulation radical newspapers for working people and the promulgation of the tactic of the general strike, “the sacred month or big holiday.”

The Newport Uprising and other attempts to use physical as against moral force have been, if not hidden from history, then at least pretty heavily disguised.

With its meticulous attention to detailed sources, its comprehensive scope and its exacting research, this book doesn’t just address the neglect of this important and interesting episode in Labour movement history but more importantly it also challenges us to think again about the revolutionary potential of the British Labour movement.

Black and Ford evidence in a way others have failed to do, the scale of the threat to the British establishment in 1839. Less than two centuries after an unlikely coalition of small landholders, Puritans, Ranters and Diggers had severed the head of an English king, this equally broad new alliance of Free Traders, Republicans, early Trade Unionists, proto socialists and working people oppressed by poverty and the Poor Law raised again the standard of rebellion.

Just as in 1648 the intransigence of Charles 1st forces his opponents to explore other means to bring about change, as the events of the year 1839 unfold, the failure of the nineteenth century state to budge on any of the basic demands of the Chartists produces a mounting frustration that inevitably leads to the exploration of other means of forcing change. The seemingly endless and at times frustratingly, meandering debates of the Chartist Convention on the options for action reflect the class forces, differing life experiences and different ideological stances represented within the early Chartist coalition. This work depicts so well the debates and debaters, warts and all.

Of course, as this book demonstrates, contingency always plays a part in any historical sequence of events. We witness the political manoeuvrings of the different factions within the Convention, the role of its leaders, with their strengths and weaknesses; the determination of some and the loss of nerve and lack of judgement of others.

However the discussions on strategy prefigure many of the future debates and controversies in the Labour movement both here and across Europe. The use of the general strike in the form of the “sacred month” foreshadows the advocacy by Rosa Luxembourg of the general strike weapon and her emphasis on the spontaneity of mass action, which has an echo of the swift mobilisations of mass protests by the Chartists. The divisions in the Convention between those adhering to moral force and those advocating physical force, if only in extremis, are repeated time and again in many major class struggles over the following century from Czarist Russia to Paris 1968.

In most accounts of the course of the Chartists campaigns it seems preposterous to compare the uprisings of 1839 with the revolutions that were to follow in many European states, Russia and China over the next century. Thanks in part to the spin within the contemporary media and the received wisdom replicated in subsequent historical accounts, the Chartist revolutionaries are looked upon largely as incompetent blunderers or fantasists.

Certainly, it is evident that many of the Convention leaders, such as John Frost of Newport, were out of their depth when it came to organising a revolution and many were orators rather than street fighters. However this book makes clear that all the evidence points to an extremely fragile British state that was unprepared for a rebellion on any serious scale and indeed was stretched to its near limits in containing protest let alone armed insurrection.

At the same time despite the exaggerated claims of some of the Chartist leaders and Convention representatives of the level of support for armed revolt in their areas, it is obvious from this research that there was sufficient combustible material amongst the working class in 1839, particularly in the industrial areas of Wales and the North, to catch the fire of revolt.

Black and Ford describe how this spark failed to light the fire of revolution but also show how close an alternative revolutionary route nearly opened up for the forward march of Labour in Britain. Decade after decade of Labour movement historiography have overlaid the Chartist story with the concept of an overwhelmingly, conservative British working class and a solely reformist British Labour Movement. The message has been consistently drilled into us that revolution was and is futile.

This book offers another perspective. Revolution in Britain in 1839 was closer than we have been previously taught. There is nothing inherently conservative in the British working class as generation after generation have mobilised to prove. What may be missing however is the learning of the lessons of each revolt and each mobilisation for change. By challenging the prevailing hegemony relating to the events and significance of 1839, this book assists us greatly in understanding the potential for future challenges to the system.

John McDonnell MP